This blog is designed to support my talk at SMACCUltimate1. The conference is held in Sydney, Australia and sadly (Ed – very sadly) it’s likely to be the very last of the SMACC conferences. The St Emlyn’s team have always supported SMACC and the work that they have done since the very beginning and many of our team have been fortunate enough to be invited to give talks or run workshops for them over the last 6 years. You can read more about SMACC and St Emlyn’s here2.

I’ve been lucky enough to speak at every SMACC conference on a range of subjects, some clinical, some educational, some political and some philosophical. This year I’ve been asked to talk on the power of peer review in emergency medicine and critical care. This is something that I’m really excited to bring to the conference as it’s something that I’ve been keen to develop and practice here in Virchester. I genuinely think that peer review, if done well, is one of the most powerful and more importantly ‘universally achievable’ tools we have at our disposal to improve our own performance and as a result the care of our patients.

Peer review is also a topic that links together several other themes shared by SMACC and the St Emlyn’s team: Personal development, Excellence3, Reflection4, Feedback5, Competence6, Confidence7, CPD and many more can be developed with peer review processes. We’ve talked about many of these issues at SMACC, outlining the difficulties and challenges of developing excellence within the emergency and critical care specialities. The purpose of my talk this year is to highlight how we can take those issues and work to develop processes that can deliver a sustainable and achievable model for personal development.

Roger Federer

I want to start with Roger Federer. I’m not really that much of a tennis fan myself, but even I know that this guy is good. As a sportsman he’s been at the top of his game for years. Think about that for a second. How has he done that? Is it because he is inherently superb? Has he just ‘got it’ with the ability to know his game and how to improve?

Well possibly, but I seriously doubt that he, or any other elite sportsperson achieved their success on their own. In sports we inherently know that coaching, evaluation and encouragement are essential components of success.

Roger Federer is one of the greatest sports stars of all time and he has a coach because he needs one. He needs the objectivity to analyse his game and to help him improve. Perhaps his success is based on knowing his strengths, weaknesses and how to work with them to improve his game.

What about you though? How do you know what to change and how to improve?

Do you really know yourself?

It’s an intriguing question that often gets people thinking, let’s start by thinking about what we are are trying to achieve – perhaps to be as good as we can be. Maslow described this as ‘Self Actualisation’ in Maslow’s hierachy of learning8 is a state whereby we reach a state of personal excellence, the point at which we become as good as we can be. In order to do that we need to understand how we perform in the world.

We all have a vision of ourselves and how we fit into the world around us. However, as we’ve discussed many times before there is a difference between competence and confidence, as famously illustrated by, the rather over-used, Dunning_Kruger study2,9. What’s implicit in that is that we cannot really understand how good our performance and behaviour is. I would take this further and suggest that it’s impossible for us to truly know ourselves, even to have the ability to sense ourselves as the world senses us.

One fun experiment to demonstrate this is the use of a non-reversing mirror which fundamentally challenges our self perception. Our visual perception of self is built from the images we see of ourselves. Photos and videos give a form of representation, but I think most people would agree that it is the mirror that provides the best representation of self. Mirrors provide a life size, 3D and accurate representation of what we look like….. except that they don’t! Standard mirrors are reflections and as such the image is reversed. Everyone knows this in relation to images, but what of faces? The truth is that every time you have looked in a mirror the image you see is a reversal of reality. When you look at your face you are looking at a reversed image and it’s not how the world sees you.

Ponder this for a second. You’ve probably never seen yourself as you really are. Everyone around you sees you in a different way, and it’s really quite a remarkably different image.

It is possible to create a non-reversing mirror using two mirrors placed at 90 degrees to each other and it’s interesting to see people react to seeing themselves as others do for the first time in their lives.

You can get an impression of what a true non-reversing mirror10 feels like to use by downloading an app like ‘True Visage’11 to your phone, or by visiting ‘realmirror.org’12 which uses the camera on your computer to do something similar. The software does not give the full experience as it’s a 2D image, whereas the physical non-reversing mirror gives a 3D image, but it will give you an impression of how the world really sees you.

The point of this rather long preamble is to reinforce the idea that our own personal perception of self is far from accurate.

The same of course goes for all aspects of our behaviour, attitudes and performance.We all possess significant cognitive biases that encourage us to reframe, revise and re-remember events that paint us in a positive light. A few years I read the book ‘Mistakes were made, but not by me’ which is an excellent summary of this cognitive reframing that we all unknowingly (and sometimes knowingly) fall victim to. Think about the last time you got into a heated discussion with another speciality. It was all their fault right because they are idiots……., except they’re not. Some of the time they’re right, and a lot of the time they will be partially right. You can quite easily spot their flaws whilst simultaneously absolving yourself of any blame!

What’s this peer review thing anyway? Does it mean the same to me as it does to you?

The primary purpose of peer review is to improve the quality and safety of care. Secondarily, it serves to reduce the organization’s vicarious malpractice liability and meet regulatory requirements. In the US, these include accreditation, licensure and Medicare participation. Peer review also supports the other processes that healthcare organizations have in place to assure that physicians are competent and practice within the boundaries of professionally accepted norms13.

In the NHS Barry McCormick Professor of Healthcare Economics in Oxford argued for the power of peer review in healthcare systems14. He invited us to think how peer review can be used to assess and develop systems and pathways in the NHS. The principles though apply equally to individuals as they do to larger systems. Indeed, in the introduction by Sir Donald Irvine the peer review principles are grounded in the professional development and aspiration of excellence amongst surgeons who sought to avoid complacency in their practice

These examples, and more, have taught me four things. First, seeking to improve one’s practice by comparing it with others can be strongly motivating, thus adding to the enjoyment, as well as the effectiveness,

Sir Donald Irvine CBE

of practice. Second, and perhaps as a direct result, doctors who have willingly engaged in good peer review come to see it as an inseparable part of their professionalism, of their identity as clinicians seeking excellence for the benefit of their patients beyond the imposed essentials of external regulation. Third is the power of data in bringing objectivity and rigour to the process. Without the discipline that reliable data bring, peer review can so easily slip into the realm of subjective discussion and opinion, thus limiting its usefulness. Finally, on the downside, it was, and still is, a minority activity largely limited to volunteers in the medical profession; the patients of doctors and other health professionals who show no interest in peer review are therefore disadvantaged.14

What do we mean by ‘peer’?

It’s worth spending some time thinking about what we mean by a peer in the context of peer review15. The dictionary definition of peer (as a noun) is shown below.

- a person of the same legal status:a jury of one’s peers.

- a person who is equal to another in abilities, qualifications, age, back-ground, and social status.

- something of equal worth or quality:a sky-scraper without peer.

- a nobleman.a member of any of the five degrees of the nobility in Great Britain and Ireland (duke, marquis, earl, viscount, andbaron).

- Archaic . a companion.

In peer review we probably think that the second definition is the most applicable, but to some extent we need a process that encourages a different perspective and different experience to our own.

When we think about our own abilities then we judge them against our own values and experiences. That’s a problem when we think about improvement as we are hardly a good judge of ourselves. The same might be said of a peer review from someone who’s experience, values and behaviours are the same as yours.

Ideally you want someone who can add value to your practice, but what does that mean. In some ways it depends on what it is that you are trying to improve.

- Clinical competency

- Scope of practice

- Communication skills

- Team Leadership

- Knowledge

- Skills

- Attitudes

- Relationships

So you ideally want someone who is competent in whichever area you wish to focus on, but you also want to someone who has a different perspective. There is less to be gained by being peer reviewed by someone who thinks and acts the same as you, as there is by someone who has a different skill set or who sees the world differently to you.

You might think that this means that you need someone who is independent of you and your normal practice. Perhaps someone from another country where their practice. However, practically you are probably not going to be able to conjure up a Chris Hicks or a Vic Brazil into your resus room. If you’re going to make this happen, and if you’re going to make it sustainable then the resources are going to have to come from closer to home. The people in the department you work in, or perhaps neighbouring hospitals or other visitors.

In contrast there are strong reasons to have peer review conducted by someone who does know you and the systems you work in. As an emergency physician I share many of the same beliefs and values as every other emergency physician on the planet. We are one tribe. We are also very different and adaptable according to the health system we work in. I’ve been lucky enough to travel the world and to visit different emergency departments like Mitchell’s plain in South Africa16 where the skill set is certainly different, but also the behaviours and interactions between team members was different too. What would ‘work’ in South Africa to get things done, might fail in Virchester. That’s not say that there is nothing to learn from different health economies. It’s just that excellence, notably in the attitudes, behaviour and relationship domains is contextualised in the culture of the department you work in.

Relationships

Learning’ cannot be abstracted from the social relations within which it occurs ‘17. This is really important when we consider how peer review will work as a process and how the outcomes may be formed and interpreted. Within any part of a peer review process the judgements made, the way it is fed back and the manner in which any suggestions or ideas will be values (and thus whether they will or will not be adopted) will al be influenced by an a-priori relationships that exist between the participants.

Hierachy and in particular how hierachy is viewed and valued within an department is an important influence here18. There will always be a degree of power distance between participants in peer review. That distance will be influenced by a whole range of different factors, some of which are listed below.

- Seniority

- Age

- Grade

- Perceived ability

- Respect

- Communication skills

- Departmental culture

- Reason for peer review (e.g. enhancement vs. remedial)

- Prior response to peer review/feedback.

My belief is that peer review to aid self actualisation works best when there is limited power distance between participants and whilst all of the factors above may increase the perception of that power distance none are insurmountable. The St Emlyn’s team is a good example of this. We are quite a varied bunch that span nearly all of the factors above and yet we have always promoted a flat hierachy. Our preparation for talks such as those at SMACC typify this.

For big talks we will develop ideas and thoughts using the P cubed model developed by Ross Fisher19. We start by developing the narrative of a talk largely on our own, but with additional help and support from the group (P1). Once this is developed we then create the media required (P2) and practice (P3) until we are ready to perform the talk in front of colleagues. Typically we do this face to face, but as we are now somewhat geographically dispersed across the globe it can be done by Skype. What comes next is the peer review process that is ‘very’ open, honest and at times pretty tough to hear. That process only works because there is little or no perceived power distance between the participants. There is no malice between the participants and the process is outcome based to deliver the best presentation we can to the audience.

This process has led to some profound changes in our presentations. I remember Rick Body bringing a talk to the group prior to SMACC in Chicago and as a group we really did not ‘get’ the underlying theme that ran through the talk (it was the parable of the good samaritan which we thought would not translate well to the international audience). On the basis of this Rick changed the entire presentation, keeping the core content but using a different theme to bring the various elements.

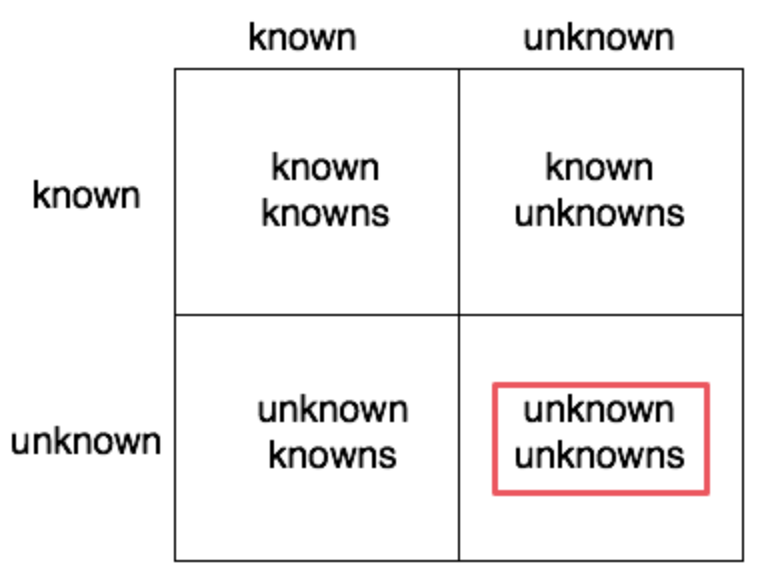

The known and unknown unknowns

It’s worth revisiting the diagram below. It’s the fairly well known demonstration that there are things we know, things we don’t and our understanding if these also differs between known and unknown. One of the questions I’ve frequently asked myself is how to gain insight into my unknowns and the answer is that I cannot do this alone. It is only through the eyes of others, through the observation and critique of my practice that I can gain such insights. In short, if I want to achieve insight at a stage before that lack of insight results in a problem then I simply cannot do this alone. I need the wisdom of others

Purpose

For some readers the idea of peer review will largely focus on the maintaining minimal standards. In some health economies the concept of peer review is in determining whether a clinicians work is up to an acceptable standard (for acceptable read minimal), and clearly that can be done when we are trying to judge whether a clinician may be a threat to patient safety.

However, that’s not what I am talking about and it’s not where I see the power of peer review. For me it’s about a process of continuous improvement and development. It’s about understanding how and where we can maximise our practice and our potential as clinicians.

Development not Judgement.

Let’s stop and think about the process of peer review and how that relates to outcome. In order for us to understand what is going on, what is good, what is not so good then it is obvious that some form of judgement against a standard is required. However, we should draw a clear line between evaluation and development (or coaching if you prefer – read more about the different types of feedback here7). The point is that in order to help someone develop then there is always an element of evaluation/judgement, but that it not the goal. Peer review should use evaluation/judgement to direct and develop the participants decision making and performance.

It helps to understand this in terms of the difference between supporting the development of clinical process rather than outcome.. We’ve previously talked on the blog, and in presentations about the difference between process and outcome. Good or bad outcomes are a mixture of luck and decisions. We need to help people develop their judgement and so try and take luck out of the equation. That is why we need to be in the room when decisions are made such that we can understand not just what was decided, but also why.

In essence when we look at a patient outcome, it is really a combination of judgement plus luck. You can have poor judgement and still be lucky such that the patient does not have a bad outcome – e.g. a patient with a head injury who meets criteria for CT scan, but you don’t scan them, but because they luckily did not have an IC haematoma then no harm happens.

Similarly you might decide to prescribe a drug to a patient who then has a massive anaphylactic reaction and dies. It was the right decision but bad luck.

The bottom line is that process is not the same as outcome, but when we are performing peer review it is the process that we are interested in. It’s not whether a decision turns out to be correct in retrospect, it’s more important to assess whether it was the right decision at the time, and why that decision was made.

How to do it

Let’s keep this as simple as possible. Think about your workplace and for most of us there will be times when we can ask a colleague to step in and just watch what happens. Sure we could make it more complicated, more difficult, maybe add some forms and some video to aid debriefing, but I don’t think it’s needed. Plus, the more complicated you make a process the less likely you are to achieve it.

In Manchester we use a very basic checklist to take notes on, but it’s not essential to use any particular tool. However, some form of record has advantages as it can be given to the person who has been observed to allow reflection and for them to put in their portfolios if they wish. If you don’t want to produce something new, then why not use your sim debriefing forms? The content is likely to be very similar and they also give a bit of structure to the conversation.

So why emphasise this technique now?

I think it’s really important that we think hard about how we translate all the wonderful learning that we get from going to a conferences like SMACC back into the workplace. I’m not sure how you do that in your practice, in fact do you do it all? Considering the cost and the environmental impact of attending an international conference I think we should feel a duty to actively share and promote our privilege with others. For example, the environmental impact of my trip to Australia put over 10 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. We need to ensure that such costs are not wasted. I see peer review working to achieve this by translating lessons learned directly to the bedside and patient care. That link is important.

I’d also look to some of the older practitioners amongs ust, and I really don’t mean that old. As a trainee we get observed, get assessments and have to jump through many different hoops in order to progress to qualification. That might be your fellowship or professional exams or board certification, but at some point you are deemed qualified. You have all the toys in the pram and you are considered good enough to be an attending or consultant.

What happens then?

It’s always struck me as odd that that process seems to stop at the point at which you become a consultant or attending. DO we really think that we are at the peak of our careers at the moment we get board certified or become a FACEM or FRCEM?

In fact there is a relationship between age and performance. Studies from medicine and surgery suggest that clinical abilities rise in the early part of the senior part of your career, but they fade with time20–23. There are many reasons why that might be. Some will be physical, many are cognitive. there are associations between this drop off in performance and adherence to guidelines, up to date knowledge and acquisition of new skills. In other words as we age in medicine our performance may diminish, but if we don’t really understand how we perform how can we possibly improve, or even keep up to date.

So for the older readers of the blog, ask yourselves when the last time was that you were directly observed, by a peer, with feedback on your performance? For many the answer will be years or even decades and that does not feel right to me.

So how do you know if you’re any good if you’re not using peer review as part of a plan to understand your performance? And if you find that a challenging question then good, it’s designed to be.

Final thoughts

Peer review is a technique that can translate knowledge and embed learning that can help you understand your own performance and that of others. It can give you an insight into how you really perform in the real world.

It’s cheap (almost free), achievable in almost any setting, applicable to all the tribes, specialities and health economies that we work in, it requires no special tools and can be used at all stages of training and indeed post qualification.

If I told you that you can do this next week would you be prepared to give it a go? I hope so and if you do, then let me know how you get on.

Finally I’m going to come back to Roger Federer. I do not know how he came to be the world’s best tennis player, nor how he managed to stay at the top of the world rankings for so long, but I’m pretty certain he did not do it alone. I’d suggest that his success is based on expert help, feedback, support and advice from coaches, colleagues and peers in the world of tennis. I’m also pretty certain that he still does that to this day.

So if you’re better at medicine than Roger is at Tennis then great. You can forget everything I’ve said. If you’re not (and I’m not) then maybe peer review might work for you.

vb

S

PS. I anticipate that the talk from SMACC will be out on their website sometime later in the year. It was only a 15 minute session on the day and so the SMACC talk is more condensed than the blog here. Keep an eye out for the SMACC talks over the coming year.

References

- 1.Home – SMACC Sydney. SMACC Sydney. https://www.smacc.net.au/. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 2.SMACC conference. St.Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/?s=smacc. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 3.Carley S. The pursuit of mastery. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/the-pursuit-of-mastery-through-deliberate-practice/. Published 2015. Accessed 2019.

- 4.May N. On Reflection. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/on-reflection/. Published 2018. Accessed 2019.

- 5.May N. Testing, testing. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/testing-testing/. Published 2013. Accessed 2019.

- 6.May N. In pursuit of excellence. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/in-pursuit-of-excellence/. Published 2018. Accessed 2019.

- 7.Carley S. How to coach and feedback to your team. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/how-to-coach-feedback-team-st-emlyns/. Published 2017. Accessed 2019.

- 8.Carley S. Educational theories you must know: Maslow. St.Emlyn’s • St Emlyn’s. St.Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/better-learning/educational-theories-you-must-know-st-emlyns/educational-theories-you-must-know-maslow-st-emlyns/. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 9.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121-1134. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10626367.

- 10.Non-reversing mirror – Wikipedia. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-reversing_mirror. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 11.True Visage. App Store. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/true-visage/id378867398?mt=8. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 12.My face that I see is different. How to see “real face.” Real Mirror. https://realmirror.org/. Published March 3, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 13.Clinical peer review – Wikipedia. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinical_peer_review. Published 2019. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 14.McCormick B. Pathway Peer Review to Improve Quality. The Health Foundation. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/NQB-12-05-01-a.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 15.Wikipedia TFE. Peer review. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer_review. Published 2019. Accessed 2019.

- 16.Carley S. Mitchell’s Plain EM. St Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/mitchells-plain-badem-and-my-utmost-respect-st-emlyns/. Published 2017. Accessed 2019.

- 17.Webb G. Theories of staff development: Development and understanding. International Journal for Academic Development. May 1996:63-69. doi:10.1080/1360144960010107

- 18.Siddiqui ZS, Jonas-Dwyer D, Carr SE. Twelve tips for peer observation of teaching. Medical Teacher. January 2007:297-300. doi:10.1080/01421590701291451

- 19.FIsher R. P Cubed presentations. ffolliet.com. http://ffolliet.com/. Published 2019. Accessed 2019.

- 20.Aiken LH, Dahlerbruch JH. Physician age and patient outcomes. BMJ. May 2017:j2286. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2286

- 21.Tsugawa Y, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM, Blumenthal DM, Jena AB. Physician age and outcomes in elderly patients in hospital in the US: observational study. BMJ. May 2017:j1797. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1797

- 22.Choudhry N, Fletcher R, Soumerai S. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260-273. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15710959.

- 23.Southern WN, Bellin EY, Arnsten JH. Longer Lengths of Stay and Higher Risk of Mortality among Inpatients of Physicians with More Years in Practice. The American Journal of Medicine. September 2011:868-874. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.011

I really enjoyed this blog, and peer review is something we are starting at BSUH EDs. However I haven’t come across a useful structured tool for feedback on clinical/shopfloor practice. Obviously it’s not essential but might be useful. Anyone do similar and have something useful?

Pingback: May 2019 Podcast Roundup. St Emlyn's • St Emlyn's

Pingback: JC: Hindsight bias. St Emlyn's • St Emlyn's

Pingback: Del 3 (Communication = Respect): Feedback, præsentation, ISBAR og ABCDE – Akutmedicineren.dk