This week I am in the beautiful city of Graz in Austria at the 9th Kongress der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Notfallmedizin (congress for emergency medicine). Simon Orlob has co-ordinated the visit (follow him on Twitter, he’s doing amazing work in Austria). Emergency Medicine in Austria is still a fairly young speciality and that’s reflected in the dynamism and enthusiasm that you can feel amongst the delegates. I’m giving two talks, one on the response to the Ariana Grande bombing in Manchester and the second on teamwork and feedback in the ED.

This week I am in the beautiful city of Graz in Austria at the 9th Kongress der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Notfallmedizin (congress for emergency medicine). Simon Orlob has co-ordinated the visit (follow him on Twitter, he’s doing amazing work in Austria). Emergency Medicine in Austria is still a fairly young speciality and that’s reflected in the dynamism and enthusiasm that you can feel amongst the delegates. I’m giving two talks, one on the response to the Ariana Grande bombing in Manchester and the second on teamwork and feedback in the ED.

The title of the talk ‘How to Coach your Team’ was given to me, and it’s a good place to start, but it’s not all about coaching as we will discover. This blog is designed to support the talk on coaching (well actually it’s about feedback) as there is only so much you can get across in 20 mins. I can’t really talk about coaching and improvement unless we place it in the wider framework of feedback and performance improvement. My aim is to inspire people to think differently about how they give feedback, but more importantly (and this is the big game changer folks) how they receive feedback. We are going to change the feedback discussion from simply how we give it, to one about how we give and receive it. Only when we understand both will we get to the stage where we can maximise its potential for lifelong learning and development.

Most, if not all of this is based on what I have learned from Natalie May who set things off back in the early days of St Emlyn’s. I’ve also taken a lot from many others, especially Chris Nickson and his suggestions to read ‘Thanks for the Feedback’ which is book I would strongly recommend you find time to read.

Why do we need feedback?

This might seem like an obvious question, but stop and think about how you work with feedback in your practice. What sort of feedback do you get at work, at home, on the sports field or with your hobbies and think about how that has changed over the course of your career? In truth we get feedback and advice all the time. It might take the form of formal assessments such as exams and annual appraisals or it might be less formal when some thanks you for doing a good job (or not). It may even be a ‘swipe right’ moment (apparently that’s what the youngsters do these days, I don’t really understand). The bottom line is that we get feedback all the time and much of it is welcome, but sometimes it just doesn’t work well.

So let’s get some fundamentals out of the way first. Ask yourself the following questions.

- Are you any good at what you do?

- How do you know?

- How do you know what you need to improve on?

- Who is going to tell you?

- How do you compare to other people in your position?

I’m happy if you want to ask those questions about your job, your hobbies/sports or even your relationships. It doesn’t matter what you think about so long as you recognise that these questions are actually pretty hard to answer from your own perspective. It’s really hard to look out and see yourself as the world sees you. In contrast the rest of the world has an amazing insight into how you perform, look, interact and achieve. The bottom line is that you cannot truly see yourself without the feedback of others.

We know this from sport of course. There are few, if any, high performing sports stars who do not have a coach/mentor/guide to help them improve their performance. Roger Federer is a great tennis player, but he still has a coach. Sports players need coaches for objectivity and guidance on how to improve. He also plays in sports where the outcomes and thus the evaluation of overall performance is clear and easy to understand. He either wins or loses and there is a simple score and record to show this. We don’t have that so clearly in medicine, but think how much we could develop if we better understood where we fit into the rankings in different aspects of our work. Finally as a sports star Roger gets the adoration of many fans, he gets feedback that can motivate and encourage him to perform better in the future.

So here is questions 6 & 7 for you to reflect on at this point.

6. Roger Federer is an awesome tennis player and yet he has a coach. You are a clinician. Do you have a coach?

7. If you don’t have a coach does this mean you are better at medicine than Roger Federer is at tennis?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeFMrkvPADg

Why does feedback feel so good?

Errr, it doesn’t. That’s the truth isn’t it. As the bible states ‘It is more blessed to give than to receive’ this does not feel the same when we are getting feedback at work or at home and here in lies a huge paradox that we need to front up to. We all know that feedback is important, and we think that as educators it is our duty to give it, but in general when we get it given to us then the whole experience may be pretty challenging especially when it is poorly delivered, poorly constructed or just plain wrong. Stop for a moment and have a think about these two mini exercises.

- Think about a time when you got feedback that made you feel good, something that made a powerful difference to your practice.

- Think about a time when feedback really hurt. Did it still make a difference to you?

In Austria we played a short game where we asked delegates in the audience to turn to each other and give them feedback on the way they were dressed and on their general appearance. This was designed to develop a whole range of emotions and experiences amongst the delegates and to help us move on to the next stage of understanding feedback types.

Types of feedback

One of the reasons why we sometimes struggle with receiving and giving feedback is because we lose sight of what the purpose and intention of the feedback is. Broadly speaking I like the categorisations from ‘Thanks for the Feedback’ which differentiate between 3 types of feedback that we experience.

- Appreciation: Gives you motivation. Sometimes you just need to be told you are doing a good job. You want to feel good about what yo uare doing. Think about when you were a kid and you had just learned to do something new like ride a bike. What didn you want and need then from your parents? It was probably some support and encouragement. You were amazing, trying hard and getting somewhere. Well done you.

- Coaching: Gives you direction to grow, learn and change. This is often what we think of as feedback and is the focus of a lot of the formalised assessments that have crept into UK medicine.The purpose of coaching is for you to understand what you have done and then use that knowledge to improve or reinforce your performance. There are many ways in which this could take place but the point is that coaching is designed to lead to a change in performance.

- Evaluation: Measures you against expectation. This is where we try and understand how we perform against a standard or perhaps against each other in a ranking system. To some extent there is always a bit of evaluation in a coaching or appreciation feedback system but it’s not necessarilly the focus of those conversations.

Understanding that feedback comes in these broad groups is really important in understanding when things don’t go well. If you ask for feedback in the hope that were going to get appreciation and then you get a whole bunch of coaching how is that going to make you feel? If you are not in the right frame of mind to receive an evaluation and you get one will that make you feel better and understand how to improve? Even appreciation can be meaningless of what you really wanted was coaching. You might think that you want feedback on how to improve your intubation technique and all you get back is ‘well done’…. really? What use is that.

This disconnect between the giver and receiver of feedback has been an epihany for me. It’s really helped me understand why some conversations work (when we are aligned) and when they don’t. Weird as it seems, if someone now asks me for feedback I spend a fair amount of time asking them what sort of feedback they want and also what specifically they want feedback on.

A good example recently at the #badEMFest18 was with a speaker who asked for feedback on her talk the day before she gave it. I think she was expecting a ‘sure, no problem’. What she got was a 10 min interview where we discussed what sort of feedback she wanted (a bit of appreciation, but mostly coaching) and then some specific thoughts and feedback on a challenging moment in the talk that could lead to a real emotional response in the room. We talked that through and then when it came to feedback that really worked. We did not do the feedback straight after the talk, but waited until the next day once all had settled down and ran through what mattered to us both. It worked really well as we were able to explore not just what went well, but why it went well, together with a few ideas for future talks (it did help that it was a really amazing talk though).

So. Next time you are asked to give feedback, or if you ask for feedback, be really clear about what type of feedback you want and ideally have that discussion before the event takes place.

In Austria we took time at this point to redo the feedback exercise about appearance with a different partner, but this time did the exercise from the perspective of the person receiving the feedback asking for a particular type of feedback and, if asked for, an area of focus for that feedback.

Spotting the good stuff.

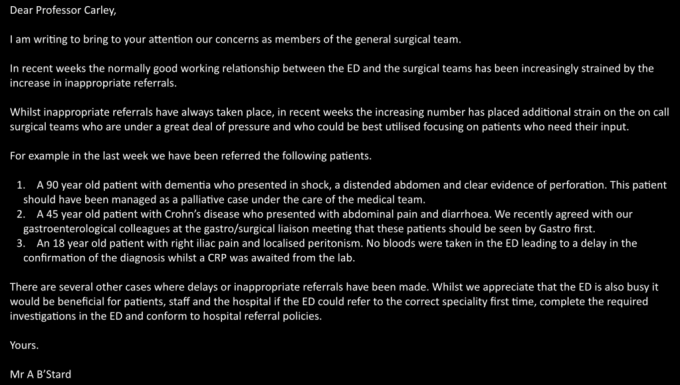

Here is a fake letter written to the ED. Have a read and then stop and think about how you would feel if this letter turned up on your desk tomorrow.

If it’s anything like me then you’re pretty angry at this point. How on earth can the surgeons write anything so stupid? How can they not understand the stresses that we are under and why are they making decisions about our patients without talking to us about them!

If it’s anything like me then you’re pretty angry at this point. How on earth can the surgeons write anything so stupid? How can they not understand the stresses that we are under and why are they making decisions about our patients without talking to us about them!

I chose this example as ‘The Surgeons’ because we often attribute behaviours to a group rather than an individual as a way of us finding fault with what is said and in trying to undermine the feedback that we are getting, because this is a form of feedback and it hurts. Someone is criticising your service and you and that hurts. At this point it is tempting to go into what has been described as ‘wrong spotting’. We go back and find all the reasons why they don’t understand and why they are wrong, but that’s no way to understand and get feedback. An alternative approach is to go back and try and ‘right spot’ the information here. Once you’ve calmed down then go back and have another look and see if there is any validity in the comments (there is) and perhaps we could do things differently in future. That ability to right spot difficult feedback is an powerful way of improving your performance. It can tell you how the rest of the world sees you and can shed light on any blind spots you have about your performance.

So. When you get feedback that you don’t like then sure find what’s wrong with it and vent your anger for a time, but then go back and look for the good stuff, the painful stuff, the truthful stuff. This is where the real gold in feedback may lie, in ‘right spotting’ your feedback.

Feedback in teams.

Simon Orlob did ask me to talk about how to improve the team and that means that we need to go beyond simply thinking about individuals into how we look to understand and improve interpersonal and team performance. There are reams of literature out there, especially around how we do this in simulation settings which I can’t and won’t go into here. Rather, I wanted to talk about practical things that people can do in the workplace to get feedback on themselves and how their teams perform in the resus room.

For example, take the role of a resuscitation team leader and ask yourself those same 5 questions we started with about your role (or consider it from the perspective of someone you see taking on that role)

- Are you any good at what you do?

- How do you know?

- How do you know what you need to improve on?

- Who is going to tell you?

- How do you compare to other people in your position?

It’s really hard to answer these questions without some way of getting feedback on how you perform. When you are acting as team leader there are often so many things and people in motion around you that it’s almost impossible to have enough bandwidth in your brain to stop and also self-analyse your performance. This is so self evident when you think about it, but we just don’t do it in most settings. There are some interesting projects around to video resuscitations and to then give feeback on performance but they are not widely used owing to financial and consent restrictions.

What you can do is peer review your performance. In practical terms this means someone of equivalent experience and understanding coming to watch how you perform as a team leader and then gove you feedback on how it went. Peer review is important as when you reach the higher levels of medicine you need someone who has an intimate understanding of the role and its challenges. This extends beyond generic human factors feedback and encompasses subject specific and locality specific performance.

What you can do is peer review your performance. In practical terms this means someone of equivalent experience and understanding coming to watch how you perform as a team leader and then gove you feedback on how it went. Peer review is important as when you reach the higher levels of medicine you need someone who has an intimate understanding of the role and its challenges. This extends beyond generic human factors feedback and encompasses subject specific and locality specific performance.

I’ll be honest in saying that we don’t do this enough in Virchester for various reasons. One is time, but another is clearly that some people are scared of evaluation when they are in senior positions. Personally I think this is crazy and refer them back to the Roger Federer analogy, if we are to both calibrate the performance of team leaders across a department AND improve individual performance then we need to have ways to feedback about how we perform. There is no-one better to do this than a colleague.

However, peer review is not without its surprises. When we set it up the prediction was that it would improve the performance of the person being watched. In truth it is probably more influential on the person doing the watching. They have a better overview of what is going on, more time to think and in seeing another person work sometimes learn a new technique or tip that they were previously unaware of.

Those clinicians who have a growth mindset readily embrace peer review, they are those clinicians who are constantly learning and seeking to do better. Clinicians with a fixed mind set seemingly avoid review and thus do not improve. This is my greatest fear as a senior consultant in the NHS, I worry that I might turn into one of those consultants who stops learning, who relies on knowledge that is years out of date and who withdraws to the easy high volume cases that the managers love us to meet and street. Please, if that ever happens can someone tap me on the shoulder and show me the door…. When we are at med school and when we are training in our specialities we expect feedback from our seniors and from our assessment systems. That disappears when you become a consultant and you need to go out and re-create it for yourseld otherwise you might become the consultant that you never wanted to be.

So. Could you set up a peer review program in your department? Would you be the person to lead by example by volunteering to go first? There is no reason why not, so go for it.

Balance in feedback.

We’ve already discussed how feedback can feel really personal and how it can be upsetting to receive. That’s pretty much true for all of us when we get feedback that highlights areas where we could improve or where we are perhaps not coming up to the grade on. Most people hold onto negative feedback far more tightly than any positive feedback they receive. Many people in medicine shrug off the positives and focus on the negatives and whilst this is not entirely healthy it is understandable if our focus is in improving our performance. What it also means is thatwe disproportionately value negative feedback over positive and this means that those we give feedback too will hold onto the negative far more than the positive.

That can cause problems because if you only ever hold onto the negatives then your overall impression of the feedback culture from you and your department will also be negative. As educators and those giving feedback we need to be mindful of this and strive to get a balance to the feedback we give. Stop and consider the following questions.

- Think back to a training post you experienced. What was the ratio of positive to negative feedback from your trainers?

- Think about yourself as a trainer. What proportion of positive to negative feedback do you think your trainees experience from you?

My expect that you will give different answers to these two questions. We probably remember more of the negative than we actually experienced and so the first question is usually answered in a negative way. The second question usually overestimates the positive. There are two reasons for this. Firstly we probably give more developmental feedback than appreciation and secondly our trainees hold onto the developmental stuff more tightly.

So. If you want to get a balance to the amount of positive and negative feedback you give then you need to overcompensate in the amount of positive vibes that come out of your mouth. We would suggest (on the basis of no science but lots of experience) that if you want to be perceived as a out 50:50 in your feedback you probably need to be about 3:1 in terms of praise to criticism. Try it and see what happens to how you feel, how your colleagues feel and how the culture in your department can change.

Giving feedback in tough situations when the news is not great.

Sometimes we need to give feedback in difficult situations, perhaps when there is a problem with a colleague. These are often behavioural or interpersonal issues such as being rude, innapropriate dress, arriving late etc. These matters are really important but they are also the most challengind aspects of feedback as it is often very painful on both sides of the conversation. In those circumstances we advocate the Giraffe method of feedback which you can read more about here. Its an incredibly powerful system to address those topics that we sometimes want to keep in the metaphorical ‘too difficult to deal with box’.

The practicalities and top tips giving feedback.

Nat has covered this in an earlier blog where she talked about a mini mental checklist to go through before you embark on a formalised feedback giving session. I use this a lot as I think it’s a very sensible way of avoiding a terrible error of timing and judgement. Read more about this checklist here.

- Is this important?

- Is this the right time?

- Is this the right place?

- Am I in the right place?

Final thoughts.

My understanding of coaching and feedback has changed a lot in recent years. I spent a lot of time trying to improve my techniques in giving feedback but not enough time in understanding how I receive feedback and in how those I give feedback too receive it. With the help of Nat May and with the links below that has changed and I think it’s working, although maybe I need some more feedback on that…..

Thanks for getting this far. My final request is that you make a commitment to do something in the next month to improve the way you understand how you and your team give and receive feedback. Choose an option from the list below and commit to it by sending an email to a colleague, partner or friend with a declaration that ‘In the next month I am going to………’

If you like, send them a link to this blog and ask them for some feedback on your idea.

Further reading

This blog and the presentation are a mixture of things I have learned from Natalie May (my go to person for anything feedback related) and a book recommended to me by Chris Nickson called ‘Thanks for the feedback’. I recommend you follow the links below to read and learn more.

vb

S

Resources

- Thanks for the Feedback book.

- Testing Testing on St Emlyn’s blog

- Feedback at the teaching course NYC

Before you go please don’t forget to…

- Subscribe to the blog (look top right for the link)

- Subscribe to our PODCAST on iTunes

- Follow us on twitter @stemlyns

- PLEASE Like us on Facebook

- Find out more about the St.Emlyn’s team

- Come join us at our conference in October 2018

Really useful. As an experienced nurse, I find that there is virtually zero positive feedback, & I try to compensate by usually only giving positive feedback, making any negative stuff as positive as I can.

Pingback: #badEMFest18 Day 2. St Emlyn's. - St.Emlyn's

Pingback: Decision making theory: Men laver jeg også fejl? (Del 3) – Akutmedicineren.dk

Pingback: Del 3 (Communication = Respect) – Akutmedicineren.dk

Pingback: SMACC2019: The Power of Peer Review • St Emlyn's

Pingback: JC: Hindsight bias. St Emlyn's • St Emlyn's

Pingback: On the fourth day of Christmas... - p cubed presentations