“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where-“ said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“-so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”

– Lewis Carroll – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

This post supports my presentation on excellence from the #stemlynsLIVE conference1 held in Manchester in 2018. You can watch the video recorded on the day below.

I grew up reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and you know what? There’s a lot of wisdom in its pages. The section above resonates particularly, because when we think about our careers in critical care, we are all likely to walk for long enough to get somewhere – the question is, where do we want to get to?

As long as I can remember I’ve endured a battle between my heart and my brain on this exact topic. I can tell you from my heart that “I want to be excellent – or at least the best I can be” (they may not be the same thing) and I’m sure you are too, which is why you’re here, reading this blog, wanting to talk about this stuff.

But my brain knows I’m not there yet. In fact, my situation is worse than Alice’s situation; she doesn’t know where she’s going, but a lot of the time I have no idea where I am. Heisenberg2 might say my uncertainty is a good thing, because if I don’t know where I am, at least there’s a chance I can know how fast I’m moving – but, that movement could very easily be simply round and round, without any progress.

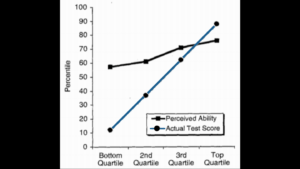

Social psychologists David Dunning & Justin Kruger’s3 Ig Nobel prize-winning work4 describes eloquently how bad we are at knowing how good we are – whether we are good or bad at something. So how can we reconcile this in medicine? And what does it even mean, to be excellent? Take a moment to think about what excellence means to you.

It’s hard to define, isn’t it? But I don’t actually think excellence is a destination. It’s a theoretical place, like Wonderland, one that changes as we explore it. Medicine is evolving and so must we, so any static definition we come up with will be outdated by the end of the week. Instead, we can draw out the elements that help us to navigate on the journey to excellence and challenge us to keep thinking, growing and changing – our personal Cheshire cats.

I think the path we walk on the journey to excellence has two parallel tracks – excellence as an individual and excellence as a team. Excellence is definitely about more than just me. So let’s walk those paths and see how we can work out where we are, where we are going, and how to get ourselves there.

Self

At the start of any journey, we need to have some idea where we are.

Locate

We have the illusion of stillness but the reality is that we are all constantly moving, constantly changing. I am literally not the same collection of cells I was when I started this sentence. So knowing where we are must also be a continual evaluation, and the key to this is reflection. Reflection is one of the most powerful tools at our disposal, allowing us to look at what is under the surface.

Reflection gives us the opportunity to replay and dissect the things we have said and done and to squeeze out every drop of learning available to us in pursuit of excellence. The aim is to increase our understanding of the self and the situation, to inform future actions.

It is natural to continue to think about the tough stuff. There are cases that confront us for a number of possible reasons and we should reflect on them. It is the way we find peace, change practice, move on and heal.

But we should also reflect regularly, perhaps on a cross section of the patients we see. The car manufacturer Toyota enacts Yotaro Hatamura’s Shippai Gaku Nososume, “an invitation to the science of failure”5. This is the concept of random sampling from your personal production line to make sure we aren’t just picking on the exciting stuff – there is plenty to learn from the mundane too. I see my juniors do this in the ED in Australia – they load up lists of the patients they’ve seen, and they review subsequent electronic medical record entries, or phone the patient they discharged to make sure things are working out.

For the tough stuff there will – and should – be an immediate phase. That’s ok, but it’s usually emotion driven. Ride it out. Share it with friends. Be kind to yourself. But don’t miss the second part – the analysis phase, after the storm.

Essentially, we want to break down the facts of what happened, the reasoning and drivers behind the facts and some future planning, but we can also be open and honest about the emotional component. It’s up to you whether you start with “what happened?” and follow with “how do I feel about it?” or start with “how do I feel?” and then “what happened to make me feel this way?”. Once you’ve fleshed out the facts and feelings, you can use a framework to thrash out the reasoning and driving forces.

At Sydney HEMS we use STEPS6 – Self, Team, Environment, Patient, Systems – to analyse cases and to identify the challenges and critical actions, because we use a similar acronym in our Zero Point Survey7.

At Resuscitology8 we use GPAS:9 Goal, Plan, Action, Skills. This model moves from macro to micro, to allow us to really plan better for next time and it’s GPAS I am going to use to explore a plan from a macro goal of excellence to a micro goal of skills, and some practical things we can actually do, to achieve that goal.

Because the final challenge of reflection is to consider the future and to ask “what will I do differently?” or “what will I take forward from this situation?”. The answer may be nothing – but that’s pretty unlikely.

Goal

So now we know where we are and we know our goal is excellence.

Plan

So we can start to plan how we are going to get there. But I don’t think we should make that plan alone. Because it’s all well and good thinking about ourselves and our practice, but we do that in the bubble of our own perceptions of our value, skills, and attitudes – and we know, thanks to Dunning and Kruger, that we really have no idea whether that bubble is floating high in the sky or part of a pigsty.

Informal peer review can be helpful. At Sydney HEMS, we have daily “coffee and cases” discussions, facilitated by our staff specialists but an open forum for our staff to bring their tricky cases and chat through the details.

If you have a mentor (you should – and ideally more than one!), they might be a good sounding board for the tough stuff. Choose the person who knows what it’s like to work how and where you do, and who cares about you enough to be honest but kind.

And finally – my passion and the topic of my future PhD; peer observation. We train for years under supervision only to specialise and be set free to drift away, hoping we are still providing the best care we can. I have worked with colleagues open enough to work on direct observation at consultant level; something we both learned from. I’m hoping to have a framework to help you do this in the next few years.

Action

What’s our action – what do we need to actually do, to enact this plan for excellence?

We need to identify our comfort zone – and step into the fringes. That might be a physical place, like the department you work in, or a practice area – like prehospital, or paediatrics – or a mindset. There’s little more humbling than turning up to work in a department as a consultant and realising you have no idea how or to whom to refer your patients, how to arrange follow-up for a fracture because the hospital doesn’t have a fracture clinic, which troponin assay is being used and what is considered an acceptable rule-out strategy, or how to prescribe antiemetics because cyclizine is not available. This has happened to me, over and over again in the last three years as I’ve started work in nine different new workplaces, organisations and departments. You can learn quickly to respect the local knowledge held by your colleagues; junior doctors and nursing and paramedic colleagues. You learn to value what you do bring to every situation; experienced decision-making and leadership skills.

Once we have stepped into those fringes, we can move beyond, into fear. What scares you? How can you confront it? This is a much bigger challenge, but you will become less afraid, I promise. It is hard. It is really, really hard. In late September 2018 I completed my third helicopter underwater escape training10. I nearly cried. I nearly walked out. But I didn’t. Credit goes to the amazing supportive crew who trained me through it – but I can take some credit for myself. I was terrified. But if I had to do it again today, I could. I’m proud of myself. What’s your fear? A sick neonate? A major trauma? How can you step far beyond your comfort zone and face it?

Skills

Understanding the limits of our comfort zone will help us then identify the skills we need to deal with our fear. We can divide this into body and mind, which is (of course) an artificial division because they are interlinked.

Body

In Wonderland, Alice ate cookies and they made her smaller.

When it comes to skills, there’s some logic to focusing on the big stuff we might be overlooking. For me it’s ultrasound, and I just need to get myself together and make an effort to get better and more confident – by spending some time upskilling, it’ll make it a far smaller deficit.

And similarly there’s small stuff too, that might make a big difference. Alice drank a drink, which made her bigger – there are some small things I’ve started to make my “always-do”: always sit down when talking to patients, always introduce myself to everyone in the room and shake all the hands, always read the discharge letter with the patient and explain all the medical words (and give them a copy). Small things can make a big difference, and in the theory of marginal gains I’ll probably get a better return than trying to become a sono whizz.

Mind

To upskill our minds, we need to challenge our mindset. Who are you in your department – in the context of your story? Are you always curious, like Alice? Be honest with yourself.

I know I can be, and I have been, a stroppy nightmare, much more like the Queen of Hearts or the Mad Hatter than like Alice, sometimes blunt – sometimes dismissive. But we can change that. If you write your own daily mantra and you will start to embody it.

How do you think:

- about yourself? Every day I tell myself “I am a kind and caring, competent doctor.”

- about what you do? Every day I tell myself “I am privileged to be here, doing this work, and I am up for this job/challenge/patient. This is why I am here.”

- about the people you work with? Every day I tell myself “I am fortunate to work with these people. Everyone here woke up this morning wanting to look after patients well.”

Say it to yourself daily and you’ll start to believe it – and that provides you a far stronger platform to deal with the emotional and human factors challenges that make up our work.

Self – Locate, Goal, Plan, Action, Skills

I think if you take yourself through this process, you can start to develop a plan for excellence with some meaningful steps we can actually work on.

Team

We don’t work in isolation in critical care, so it’s important we recognise how our teams contribute to excellence. This is the parallel track to personal excellence on our journey.

Locate

In terms of knowing where we are before we start, audit is probably our strongest tool. Audit allows us to set standards that make sense to your organisation, then measure yourselves against them. Sydney HEMS has KPIs around prehospital intubation, and around scene times.

Goal

Again, we know we are aiming for our goal of excellence…

Plan

…we can start to plan how we are going to get there.

Clinical governance is key to knowing not only where your team is but also how it is going to move towards excellence. Departments do this in different ways; in Oxford at the John Radcliffe, the ED had a monthly clinical governance day where we analysed every death in our department and presented challenging cases. This is effectively measurement and peer review in one, and governance days happen in most places in some form. It’s worth thinking about how organised and accessible it is where you work. At Sydney HEMS, we have dial-in options for our staff on other bases or at home – the details are only shared within our staff.

Our M&M sessions contain powerful and valuable learning that we may be able to use to change the way we practice as an organisation – but it takes time and effort to extract that learning. We talk through the cases to identify ways we need to change – or the great stuff we need to do more of. We just shouldn’t look at the bad without the good – we also want to talk about the great “saves”, the A&A – and that’s something we do regularly at Sydney HEMS as part of our governance processes.

When we are learning from our governance processes, openness is key; anonymising cases so the individuals concerned with critical incidents cannot be identified can be very helpful in promoting frank and honest discussion. But I would challenge you to de-anonymise yourself. Taking responsibility for the care you have provided can be very empowering in M&M discussions and I have found that I experience more curiosity and compassion with my non-anonymised cases than when there is a nameless, faceless doctor at the heart of a case discussion.

Research sits alongside audit and risk management in clinical governance, asking where your team or organisation fits into the wider world picture. Good quality primary research is a lot of hard work, but teams who do it see tremendous benefits.

Action

In order to make meaningful and lasting change at an organisational level, we first need to consider culture: what we do and the way we do things. Culture is a nebulous term to many of us but it is critical to the way our teams and departments function and determines our ability to enact change.

At Sydney HEMS this culture is reinforced by regularly and explicitly sharing our core values. The language we use matters. We have structured daily brief that discusses risks to our operations, and our flight crew conducts a mission risk assessment before we receive any patient details, so that we can make objective decisions about safety. We have shared understanding of what safety means – four to say go, one to say no means that if something is to be undertaken operationally, all four crew members must be agreed for it to proceed, while a single crew member can stop the process by expressing their concern.

Culture goes far beyond safety, but our safety culture is a good example of how embedding shared values can shape decision-making. What is the culture like in the places you work? What are your core values; how are they shared? How are they expressed?

Skills

Body

What skills do we need in order to shape our team’s culture, and to help our team embody it?

Training our teams in clinical skills can help them to free up the bandwidth to address behaviours, to embody our organisational culture and make the changes we want them to.

Teach big stuff: life, limb and sight-saving procedures. They are rare, but confronting, and we need a degree of mental preparedness as well as muscle memory and physical preparedness. Formal simulation is our best tool here, considering “currency” requirements. As specialists, we induct new registrars at Sydney HEMS every 6 months, so we get a refresher on thoracotomy, escharotomy, surgical airway, craniotomy, hysterotomy, neonatal resuscitation. We teach them using spaced repetition with desirable difficulties over a week-long induction programme and in doing so, we regain our own familiarity. We also maintain currency on the high-risk stuff; we rehearse prehospital intubation regularly, alongside our high-risk mission-related skills such as winching. By generating a degree of automaticity for the big stuff, we offload some bandwidth, making it available to manage the non-technical skills that often make these situations more challenging than we might otherwise anticipate.

Teach common stuff: the bread-and-butter of what you do. You can make big gains with small improvements in the stuff you do a lot – and it doesn’t just have to be clinical. You can teach decision-making, communication and teamworking alongside clinical skills. In-situ simulation is a great tool for improving the performance of your team, organisation or system, rather than individuals. At St George, we are just starting out with POP sim in our ED and already we have a huge range of ideas around streamlining and improving the care of our sickest patients. In-situ sim is not without challenges; in particular it can take some time to embed a culture of sim into a department, but it is well worth it – I still remember the sheer joy of watching our nursing staff in Manchester step up, feeling empowered to speak out for safer and better patient care.

Mind

As senior clinicians in healthcare teams, it’s easy for us to be “The Boss”. But I would challenge you that your team will gain much more if you are able to role-model perpetual learning. Sharing your uncertainty, your errors, your failures can flatten departmental hierarchies, allowing your colleagues to speak up when something doesn’t seem right, and maintaining your humility. I love the idea of asking your team “what am I missing?” and in doing so, giving them permission to save your ass.

It’s hard, because we doubt ourselves regularly and we want to overcome that by convincing everyone else that we’re all over it – but really we aren’t fooling anyone. We do our teams a disservice this way. I challenge you – and myself – to stay curious and keep learning, openly. And I want to take a moment to thank my colleagues in the St Emlyn’s team for providing me a constant platform to do that.

What Now?

I feel pretty lucky to have had the opportunities that have led me to reflect on these dimensions of what we do, but you don’t have to move halfway across the world in search of personal and organisational excellence.

We are not striving for perfection. Perfect is the enemy of good (Voltaire). And excellence is relative – it may mean different things to different people. There is no magical department where everything is perfect. No one department or organisation, here in Manchester or at any of the nine places I’ve worked since, has all of this stuff covered perfectly – and I’m certainly not perfect!

Think about what you can do for yourself – reflect, to know where you are. Peer review, to know where you are going. Identify your comfort zone, then get out of there! Reframe your physical skillset looking at the big and small stuff. Reframe your mindset.

Think about what your team can do – share in audit, to know where you are. Examine M&M and A&A, alongside research, to shape where you are going. Examine your culture and own it. Use education and role modelling to effect meaningful and lasting change.

That growth mindset, striving for continual improvement, for consistency in excellence is a much more meaningful aim than any single big win, just as excellence is a journey, not a destination. There is great joy in working with like-minded people to deliver better and better care. You can push yourself and your organisation towards excellence from where you are right now but it’s likely to be hard.

There’ll be times you don’t know how to move forward, and that’s why it’s really important that you have some support – ideally one person from inside your organisation and one from outside, for those times you need someone to point out you’re trying to play croquet with a flamingo and a hedgehog.

Find your people. Those who will sit down over tea and work out riddles with you.

St Emlyn’s Live was a great opportunity to do that, and Twitter has filled some of that role for me – but whenever you’re at a conference that makes you feel inspired, you can find buddies there too.

If there’s someone there from your organisation, have a chat with them during the coffee break – can the two of you come up with a way to help each other figure out where you are, where you need to go, what you need to do to get there and how you can develop the skills you’ll need? And if there’s no-one there from the place you work, look around – there’ll be a whole room full of enthusiastic people who can be your outside champions and your source of support as we all move forward in pursuit of excellence.

Nat

Pingback: Podcast: October 2018 round up St Emlyn's • St Emlyn's

Pingback: SMACC2019: The Power of Peer Review • St Emlyn's

Pingback: The UK Resuscitationist. St Emlyn's • St Emlyn's