If you’re a #FOAMed fan then you will have come across the term Gestalt quite a lot in recent months. Many conversations about clinical decisions hinge around this elusive, slippery and somewhat obscure term. Perhaps it is in a rather circular manner something that is difficult to define, yet we know it when we see it….., or perhaps we are merely using the wrong term.

This very brief introduction is a start on a number of future posts linking perception, interpretation, judgement and clinical decision making.

So for starters, do you agree with Linda?

Why has the word "gestalt" suddenly started popping up more and more?

— Dr Linda Dykes @[email protected] (@DrLindaDykes) June 28, 2014

It’s time to find out.

What does Gestalt mean?

Originally Gestalt means ‘shape or form’. It’s a German term that has come to be associated with a theory of perception and understanding.

Where does the term come from?

Gestalt originated in the psychological literature towards the beginning of the last century. It was a counter to the structuralist arguments promoted towards the end of the 19th Century. Structuralist approaches suggest that everything can be broken down into individual components, thus by knowing the nature of constituent parts we can understand the whole. For example a structuralist approach would suggest that by understanding all the aspects of automotive engineering we can understand what a car is. Gestalt would argue that we perceive a car as a whole and not as components. Gestalt states that our minds organise information to a global perception rather than by assessing each individual element, in other words ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’.

Properties in Gestalt systems

Much of the literature around gestalt focuses on visual perceptions and there are several examples around that you may be familiar with. There are four properties in gestalt systems, emergence, reification, invariance and multistability.

Emergence

Emergence is the phenomena where a complex pattern emerges from simpler forms. Perhaps the best known example of this is the following picture of a Dalmation dog. There is clearly no picture of dog here, but our minds are able to form the final image from the component parts. None of the components in itself is dog like, yet the sum of the image gives a dog sniffing the ground

Reification

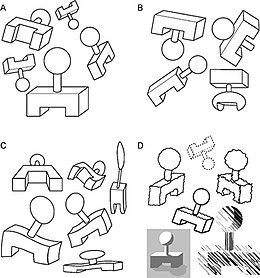

Reification is the process by where we construct spacial relationships from elements outwith those presented to use. Several examples are shown below where geometrical objects are perceived by the relationship with the components presented, yet they do not actually exist.

Multistability

Multistability takes place when we can perceive an object in a variety of different ways and its a common visual puzzle that you will be familiar with. Examples below include the Necker cube and the Rubin vase, but there are many others.

Invariance

Invariance is the property whereby objects are perceived as the same despite differences in relative shape, size, rotation scale or aspect. Similarly we perceive the same shape regardless of environmental effects such as setting, time of day, location etc.

Most work in Gestalt has focused on the visual aspects of perception but it can be recognised in other senses such as through the interpretation of sound and music.

Do such visual elements of Gestalt exist in medicine?

Arguably they do. We build towards a diagnosis from elements of its form rather than an entire picture or a consistent form. Diagnoses emerge from individual components that we bring together to a ‘form’ that we recognise and subsequently label (emergence/reification). We are often faced with constelleations of symptoms and signs that may represent one condition or another, for example in that breathless COPD/IHD/Pneumonic patient in resus (multistability), and few patients are precisely the same yet we manage to make a similar diagnosis (invariance).

How do we use it medicine?

We seem to use it a lot. Gestalt is often thought to be similar to ‘clinical judgement’, though we need to think that through a little more deeply later. It is referred to in conversations between clinicians and also appears in a number of clinical decision rules.

@JudkinsSimon @EMManchester @davehartin @docib I'm still hearing a description of what I've always thought was just clinical expertise…

— Dr Linda Dykes @[email protected] (@DrLindaDykes) June 28, 2014

@EMManchester @mmbangor @davehartin @docib Think it's a combination of education, experience, knowing the lit and gut feeling.

— Brian Burns (@HawkmoonHEMS) June 28, 2014

@EMManchester @mmbangor @davehartin @docib there are all sorts of subtle cues about disease that patients give that we don't have names for

— NodakEM (@NodakEM) June 28, 2014

Several clinical decision rules appear to encompass Gestalt. For example the PERC rule is designed to be used in a population that the clinician believes to be low risk, it then goes on to list a number of other tangible features that also determine low risk. So, if the objective measures are evidence of low risk, what then is the original perception of the treating clinician that this is a low risk patient. Similarly in the Wells DVT score we assign a score of -2 for patients in whom we feel an alternative diagnosis is likely. This soft perception on the part of the clinician is again arguably embracing Gestalt within a scoring system.

If we are looking for a simple definition of Gestalt then we can simply consider it to be a sensory interpretation that is greater than the sum of its parts (a concept which predates Gestalt and which dates back to Aristotle). In clinical terms we can define it thus: ‘A structure, configuration, or pattern of physiological, biological or psychological phenomena so integrated as to constitute a functional unit with properties not derivable by summation of its parts.’

So what might this mean in real terms. Well, I often use the silly walks example. You are walking through resus and you walk past bed 1, bed 2, bed 3, then suddenly turn on your heels and return to bed 2. Something is up…, but you not sure what. Something about the noise, sight, smell, atmosphere tells you that something is not right. The observations/monitors are either irrelevant or contradictory. You just know…, the outcome is greater than the sum of the perception.

We also use Gestalt daily in the interpretation of ECGs in the ED. Whilst we may teach an atomistic approach to our medical students. Calculate the rate, rhythm, size, relationship etc. as experienced clinicians we do not do this at all. A simple observation of a cardiologist or emergency physician reading an ECG is an example of heuristics, gestalt and judgement over a constructivist approach to data interpretation. Only when pattern recognition and gestalt fails do experts resort to systematic enquiry. There are many, many other examples within our practice that both help and hinder us as clinicians, but what is not in doubt is the importance to clinical decision making inherent within the realms of perception, interpretation and judgement.

Gestalt and the immeasurably measurable.

If Gestalt is truly greater than the sum of its constituent parts then this can only be the case where all parts are perceived, considered and valued, but that is not a characteristic of medical education. In our patients and clinical studies we have a propensity to measure and value what is measurable. Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate are quantative values which we can define and share. However, other elements of assessment which are arguably highly valued by clinicians such as agitation, sweating, distractability, attentiveness are difficult to measure, but are perceived by clinicians. Ask an experienced clinician to look at a patient in the resus room who has an abmormal respiratory pattern, sweating, agitation then they will comment and value on these findings. However, they will not commonly feature in clinical scores (which favour objective data). This is commonly referred to as Gestalt, but it is not. The signs are there, they are perceived and indeed articulated at handover and between the resus team, but they might not make it onto the nurses observation chart.

Beyond that are more subtle clinical signs such as distractability and other responses that may be difficult to explicitly perceive and share, but which a clinician may sense and use in formulation without perception.

Summary.

So Gestalt in its purest sense is somewhat contrary to the positivistic pseudo-scientific view that many clinicians hold onto as a model for their practice. Gestalt is one element and pathway that links the acquisition of data through to processing and ultimately to clinical judegement and decision making. In its simplest sense it is an assessment that is greater than its parts, but in the world of emergency medicine the term is often confused with the wider realm of clinical judgement.

References/Further Reading

- Wikipedia Gestalt Psychology

- Cervellin G1, Borghi L, Lippi G. Do clinicians decide relying primarily on Bayesians principles or on Gestalt perception? Some pearls and pitfalls of Gestalt perception in medicine.Intern Emerg Med. 2014 Aug;9(5):513-9. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1049-8. Epub 2014 Mar 8.

- Giovanni Casazza • Giorgio Costantino • Piergiorgio Duca Clinical decision making: an introduction. Intern Emerg Med (2010) 5:547–552

- Gunver S Kienle MD and Helmut Kiene MD Clinical judgement and the medical profession. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

- Andrea Penaloza, MD; Franck Verschuren, MD, PhD; Guy Meyer, MD; Sybille Quentin-Georget, MD; Caroline Soulie, MD; Frédéric Thys, MD, PhD; Pierre-Marie Roy, MD, PhD Comparison of the Unstructured Clinician Gestalt, the Wells Score, and the Revised Geneva Score to Estimate Pretest Probability for Suspected Pulmonary Embolism Annals of Emergency Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.002

- Julian N. Marewski, PhD; Gerd Gigerenzer, PhD Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2012; 14(1): 77–89.

- Body R, Cook G, Burrows G, et al. Can emergency physicians ‘rule in’ and ‘rule out’ acute myocardial infarction with clinical judgement? Emerg Med J Published Online First: doi:10.1136/ emermed-2014-203832

- Michael J. Dreschera, Frances M. Russelld, Maryanne Pappasb and David A. Pepperc Can emergency medicine practitioners predict disposition of psychiatric patients based on a brief medical evaluation?

- Gerd Gigerenzer and Wolfgang Gaissmaier. Heuristic Decision Making Annual Review of Psychology Vol. 62: 451-482 (Volume publication date January 2011) DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346

- STEPHEN G. HENRY RECOGNIZING TACIT KNOWLEDGE IN MEDICAL EPISTEMOLOGY Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics (2006) 27:187–213

- Anderson RC, Fagan MJ, Sebastian J. Teaching Students the Art and Science of Physical Diagnosis Am J Med. 2001 Apr 1;110(5):419-23.

- Christopher A. Feddock, MD, MS The Lost Art of Clinical Skills The American Journal of Medicine

Volume 120, Issue 4, Pages 374–378, April 2007

Oh, and if you’re interested in where we are going next, check out this short video based on my talk at the Exeter CEM conference.

Great article! I’ll be doing a blogpost about gestalt and the topic of split-second decision-making in the ED based on the claims from the book Blink by Malcolm Gladwell. He uses a lot of good examples, but basically, an expert in any field subconsciously breaks down a situation within seconds. We should be able to dispo a patient after only a few minutes of talking to them! More to come, check out my site edocc.com. I’ll be posting that blogpost soon. Keep up the great work!

I;ll look forward to that post Joseph.

As for Blink, I kind of like it, and it reads well but it’s greatest benefit to me has been to push to me to read wider. I would strongly recommend ‘The Invisible Gorilla’ by Chris Chabris and Daniel Simons as an antidote to Blink. It’s arguably a better book with more science in it, and some truly fascinating examples.

vb

S

I’m not sure (although I may simply have misunderstood the whole thing)

I think there is a difference between the pattern recognition of the expert, and the idea of gestalt as the ‘whole is greater than the sum of its parts’. This to me implies that the expert clinician is perceiving something that is not there, when I am not sure that this is the case.

I think the examples given are great descriptions of expert performance, where a large amount of information is processed very quickly to arrive a conclusion. This process for the expert has become tacit and each will likely have their own ‘way’ of doing things, but they can still break down all of the information in front of them and explain exactly WHY they are worried about that patient, or WHY that ECG is abnormal. The parts will add up to the whole. The experts are not seeing anything that is not there, but are simply adding up the presents information more quickly and completely to arrive at a more accurate and timely diagnosis.

This knowledge can however be broken down into parts and taught to novices, who in turn, with time and practice, will take this explicit knowledge and turn it into a tacit understanding of their own.

Whatever your views, this is a fascinating topic!

Indeed. I used to think that Gestalt does not exist, but now I am not so sure. In future blogs I’ll hopefully explain the difference and difficulties of perception vs processing vs value. I don’t think that will make a lot of sense at the moment…., but in time I hope it will.

Anyway, what awesome blog post do you have for us next?

vb

S

Wikipedia tells me that the word other can be substituted for greater as an alternative translation 😉

‘the whole is other than the sum of its parts’ makes more sense to me in the way that we use the term Gestalt in medical practice.

Looking forward to the rest of the posts.

Great work! I mentioned Daniel Kahneman & his summary book “Thinking Fast & Slow” on twitter, partially because I think there’s some relevance and partially because it gets so much discussion in the FOAM world so it warrants some discussion here.

I think what we casually call clinical gestalt is similar to but not identical to Kahneman’s “System 1” — the clinician’s initial gut reaction in the first few seconds of seeing a patient. Not to completely discount Gladwell, but he is admittedly a journalist, and Blink essentially describes the same thing for a more lay audience.

In my (relatively unrefined) view, clinical gestalt is what you think at any point during the workup or patient encounter, as opposed to System 1, which is your immediate jump to judgment. And NodakEM puts it well — gestalt is not completely ineffable, including subtle and not so subtle disease cues; see, for example, Jeff Kline’s newer work on patient facial expression and how it informs clinician decision making. To paraphrase loosely, we should all be worried when the patient looks like they’re doing their taxes. I think gestalt includes those subtle cues, the concrete pieces of information, and completely occult inputs (including biases) that we will never be able to measure. Gestalt is our final answer after looking at all of the data, whether or not it is visible.

The Kline paper in emj recently on facial expressions and how we interpret them firs into gestalt I think. I’ve been saying for years (to any poor sho who will listen) that whether patients look sick or not sick is in part down to the eye contact and non verbal interactions that occur in the interaction. Smiling at me (but only in the right way) buys you a discharge from me a lot of the time. Assuming there’s no St elevation….

Interesting post Simon – and thanks for the excuse to run away from FCEM revision, however briefly!

A couple of points:

As Seth says, your description of gestalt as above sounds a lot like type 1 thinking, albeit a highly skilled, well evolved version of it. If so, should we really be teaching/encouraging it? It will be interesting to see if Pat Croskerry addresses the gestalt issue when he talks about cognitive debiasing at SMACC. However, I suspect all of us can remember the patient(s) where all the numbers/examination/investigations were ok so the type 2 thinking would say the patient is ok but the little voice at the back of the head was screaming no? So maybe gestalt for “it’s bad” should be encouraged but gestalt for “it’s ok” should be challenged?

Second, although the original visual gestalt may be constructivist (the dalmatian will only be there if you have previously encountered the concept of “spotty dog”) I think the way we conceptualise it in medicine is still postpositivist – you are still searching for a “truth” (in this case patient badness) that you believe exists as an absolute, albeit via cues which are hard to describe 😉

And back to the revision…….

Thanks KC. Is it system 1? Well, it’s a component of it, but the two are not synonymous.

Try this as an example from the man himself.

http://www.sigurdmikkelsen.no/admin/dokumenter/NP%20-%20Croskerry%20-%202009%20-%20Clinical%20cognition%20and%20diagnostic%20errors.pdf

S

…and like you I am really interested in hearing Pat speak again.

I am also conscious that having him at the conference adds a frisson of pressure to those of us thinking in the same area.

vb

S

Gday Simon

So glad that you put this up – it is a fascinating topic. One that has important ramifications for the way that we train and reflect upon our own practice.

I have a few points I would like to make:

I’ll start with a quote from “The Princess Bride”…

Vizzini : INCONCEIVABLE!

Inigo Montoya: “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

I agree with your summary – a large part of the confusion around “what is Gestalt” stems from the fact that it has taken on a meaning in common medical parlance that is far removed from the original term which you have described nicely above.

When we say things like: “My Gestalt is that this is not a PE…. so Well’s score is low.” – I do not feel that we are really using Gestalt in the true sense – that is experience and clinical acumen – there are no hidden or missing components really.

I think the modern medical definition of Gestalt would be akin to “gut feeling”, “hunch” or “best guess in the situation”. These may include some elements of true Gestalt, a diagnostic reification if you like, but are ultimately based more on experience which is fathomable.

Second point – I agree with Dr Challen’s point above i.e. “the dalmatian will only be there if you have previously encountered the concept of “spotty dog”…

There is a lot of fantastical thinking in medicine – we see thousands of patients and have fuzzy memories. I quite often find myself thinking: ” I have seen this combination of symptom X, Y and Z somewhere….” And when I arrive at what seems like a brilliant diagnosis – it is not because I am an excellent diagnostician – it is more because I have a vague memory of a similar scenario panning out this way when I was an RMO.

Reflective learning allows us to distill these moments into learnable (?teachable) points rather than accepting the idea that we are savvy diagnosticians with great Gestalt / gut instinct.

Regular reflection allows us to develop a diverse and useful toolbox of heuristics. Accepting the concept of “gestalt gut feeling” seems a bit of a waste – decision-making becomes an exercise in faith almost.

And lastly, on the Kline facial expression studies. I tend to feel that this is really about empathy – we have an extraordinarily well developed neurological system which allows us to “feel” what a patient is experiencing. I tried to coin another German word to describe this – Einfuhlung in my SMACC talk in March. It translates as “to feel into an object”. My guess is that we all have this innate ability to read faces, posture and tone and get large amounts of valuable clinical data from it…. but… we have suppressed this capacity with our training and focus on the more traditional clinical signs and “tests” which we so love.

So I don’t think this is Gestalt – I think it is a fundamentally human skill which is well described and requires no psychological discussion as it is a neurologic phenomenon!

OK

Rant over

Will be front and centre when Pat Crosskerry and yourself talk in Chicago. Expect Twitter heckles.

Casey

Hi Casey,

I’m so grateful for you joining in as I know that you, like me, love thinking about this sort of thing.

I think it’s inconceivable that we would be too far away in our thinking and I don’t think we are. My original standpoint in Gestalt was that it doesn’t exist, but I’m coming round to the idea that it does, but not in the way that it commonly described between clinicians, researchers and bloggers.

So, less of a rant. More of a heated agreement 🙂

vb

S

Gestalt. Nice discussion, Casey! A Must read. I think for those interested in this subject, which is hopefully a majority of us, and certainly ALL educators, a good start would be to read Gladwells “Blink”, Kahnemans “thinking fast and slow”, and Lehrers “how we decide”.

The bottom line is our clinical acumen consists of a complex nexus of interconnections between cortical functions and deeper hippocampal and other areas of our amazing brains.

In other words, this phenomenon is suited for an entire subject course in medical school and beyond.

The challenge with teaching is that it is an attempt to vocalize (cortex) our complex deeper processes so that we can explain to learners how to gather and interpret the subtle data points present in the clinical setting.

An example is given in one of the above mentioned books where a baseball player would have a hard time talking someone through the complexities of his talents in hitting a curveball. The battle between cortex and deeper layers.

Think about that next time you swerve or brake to avoid a near collision while listening to a podcast in your car and fielding a phone call (hope not). Could you walk a teenager step by step through your thought processes?

I believe that the modern department setting is stacked AGAINST teaching and using Gestalt, where Doctors are spending an inordinate amount of time in front of a computer, ordering and interpreting tests, versus gathering data points at the bedside WITH the patient and soaking up the GESTALT and processing that for future encounters.

Hopefully we can reverse the trend of turning clinicians into technicians.

Fascinating stuff.

Cheers!

I would add Gerd Gigerenzer to the list of “must reads” – or any of his online lectures.

He answers the baseball analogy with a great simple heuristic that is easily explainable / teachable. Also some aviation pearls about judging landing distances in complex scenarios – it can be boiled down to a simple heuristic – which is teachable.

My feeling is that explaining clinical acumen with “gestalt” leads to a belief that ther eis some mysterious inner process that we can never really explain or teach to trainees. I would prefer to believe that we can explain our inner workings in terms that are simple enough to teach to others.

The idea of Gestalt does seem to lead to some fatalistic outcomes if it is really how we process data.

Casey

Pingback: LITFL Review 156

Pingback: When we are the Diagnostic Test - Gestalt at St Emlyns

Pingback: Gut Instinct | Wheezles and Sneezles

Pingback: akutmottagningen

Pingback: JC: Are typical chest pain symptoms predictive of outcome? St.Emlyn's - St.Emlyn's

Pingback: App in Pills – Dicembre 2015: - EM Pills

The misuse of the apostrophe in “its” is driving me crazy! Its is possessive Simon. Apart from that I really enjoyed the article & gestalt is an important component of what we do in EM. A nice commentary.

Pingback: When is a Door Not a Door? Bias, Heuristics & Metacognition

Apparently…

>The original famous phrase of Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka, “the whole is something else than the sum of its parts” is often incorrectly translated as “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”…

Pingback: Thinking: Agitation – Medic Mindset

Pingback: LITFL Review 156 • LITFL Medical Blog • FOAMed Review

Pingback: Troponin-negative chest pain: who needs further testing? • The BREACH