This week I am joining the iMED conference 12.0 in Lisbon, Portugal, except I’m not really as I am in my office here in Manchester as a result of the COVID19 pandemic. Lisbon is a lovely city with great people and amazing food, so I am a little sad about being stuck here, but I will return someday. Hopefully that will be for the EuSEM 2021 conference which is due to be held there (if not sooner).

My talk is based on one I did for the #stemlynsLIVE conference with some updates and more. I’m reposting the blog from that time with the updates so that delegates can use this for post presentation learning and links. I also hope you find it useful too.

You can see an older version of the the presentation below, but as there have been changes since I do recommend reading the links below.

This blog supports my presentation on ‘Making Resus Better’, a title that evolved from Cutting Edge evidence in resuscitation. I’ve changed the title after discovering that this is all being covered by other speakers. What do you do when that happens? You ask the best in the business for help. I reached out to Scott Weingart, Chris Hicks, Cliff Reid, Ken Milne, Youri Yourdanov and the St Emlyn’s team with the simple question….

If you could change one thing in resus to make resuscitation better what would it be?

Stop for a second and ponder that question for yourself. What would you do to improve resus outcomes for your patients. I suspect that your first thought would be around what evidence or devices have come out recently that we all need to introduce to save lives. Are you ECMO or ECNO? What about REBOA and TEG testing in the resus room? Have you introduced or changed your management of catecholamines in cardiac arrest patients? Then many hospitals are also choosing to rent medical equipment like an extra ultrasound machine as they often need extra capacity at certain times.

I think you will have gone through a few of these before pausing and thinking about how much impact any one (or even all) of those changes might make to your resus patients. In truth it’s not a lot. The number of patients who would benefit is small and the gains are arguably marginal for many of them. The lesson here is that we don’t make big changes by introducing marginal changes for small numbers of patients, we should still aspire to do so and many of the other talks today are about exactly that, but perhaps we need to think a little wider. I wanted to share our collective thoughts and ideas that we believe can make a real difference to performance without any special courses, equipment, drugs or money. Everything here is something you can do next week with next to nothing. If you’re doing them already then great, please use this post to share those ideas with as many people as you can.

The following strategies are designed to improve the effectiveness of any resus team and thus to improve the care of any patient requiring resuscitation. They will be of most benefit in cases when there are higher levels of complexity in the team, the treatments or the patient, but that’s no excuse not to use and learn them on less complex patients as that will train and embed the principles.

Zero Point Survey

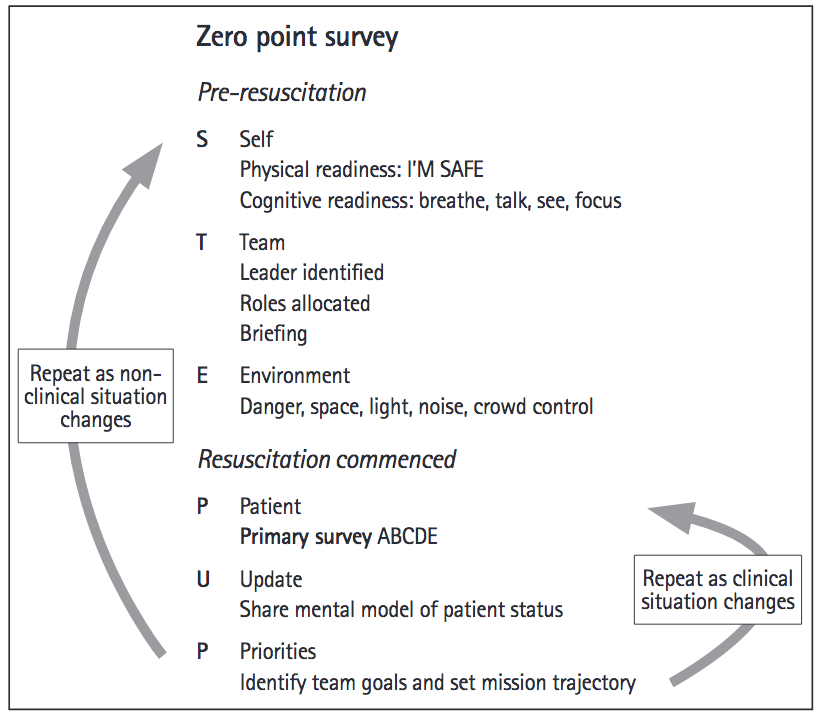

I recently blogged on this work led by Cliff Reid which you can read here1,2. The ZPS is designed to focus the thoughts and actions of the resus team from the first moment that they become aware of the patient. In the ED that’s often when the standby phone goes and we realise that something is going to happen. At that point an effective resus team will come together to prepare, assess, synthesise and plan for what happens next.

The STEPUP principles of the ZPS are shown below.

The most significant impact of the ZPS is in the preparation phase before resuscitation commences. Within that time and space the team should prepare in order to collectively improve their situation awareness even before the patient arrives. In Virchester we like to think of situational awareness in 3 ways.

- What’s happening? What info is available and am I aware of it?

- What does that mean? Synthesise the information into something that makes sense

- What’s going to happen? On the basis of ‘2’ what are the likely predictable paths for this patient in the short and medium term?

The point here is that we can often plan and predict the potential clinical courses for patients on the basis of very limited information, but my observation is that this frequently does not happen in an effective way. Let’s take an example…

The standby phone goes and you get the following message.

A 45 year old man has collapsed in the centre of Virchester after complaining of chest pain. He has had bystander CPR and a rapid attendance by a bike based paramedic. He has an LMA in place. He is currently in VF after 2 shock cycles. He has an IV in situ.

Typically the team will assemble for a standard cardiac arrest, but is that all they can do? I would argue that in this case we can predict many things. The patient is young and has presented in VF. Toxicological causes are possible (in Virchester they really are), but the chest pain might suggest an acute coronary syndrome. The fact that he is in VF means that the initial priority on arrival will be defibrillation. The age of the patient predicts a long resus time and possible PCI or thrombolytic interventions.

These predictions can and should be shared with the entire team (not just the doctors) so that they can share the same mental model. By articulating these facts to the team they can have the opportunity to generically and specifically prepare. If you think this already happens then you’re probably wrong. You can test it by reading out your next standby call to the resus team then pausing for a few seconds, get them to individually write down what they think will happen next and what the immediate patient priorities will be. I will guarantee that the team members will individually have very different interpretation on what’s going to happen next.

The self component may be as straightforward as ensuring that you are fed, watered, toileted and awake! Physiological needs are important after all. Beyond that a Self assessment involves assessing whether you are cognitively capable and ready for the likely resuscitation. If you are not and you need help then don’t be proud, ask for it. You should also be honest in what you are capable of doing and be mindful of the difference between confidence and competence. I know that lots of us want to do procedures as part of our training and development, but when a patient’s life is at stake you should only agree to do something if you are actually capable of doing it to a high standard. See the original ZPS post for an explanation and example of how that works in practice.

With a shared model of what is likely to happen the team can assess and optimise the environment in generic and specific ways. Illustrative, non-exhaustive lists are shown below based on the case above.

Generic (all cardiac arrests)

- USS machine present, plugged in, gelled up.

- Competent USS

- Step for CPR

- ECG Machine

Specific (this arrest)

- Thrombolytics out of cupboard with hospital policy for administration

- Check if cath lab staff in and current capacity

- Lines trolley

- Second defib for Dual Sequence Defibrillation

- Enough staff for prolonged resus attempt and/or LUCAS device

- Highly likelihood of early change of LMA to ETT. Need full airway kit available.

Now it maybe that you believe that you prepare everything for everybody, but I doubt it. We need a different set up and mindset for cardiac arrest in an 89 year old nursing home resident vs. a young man being brought in from a night club.

The preparation phases are closely aligned to the initial expected priorities and the generic ABC approach that we are all so familiar with.

The final two stages of the ZPS are based on updating the team and prioritising tasks which I will explore in more detail below.

The ZPS puts a name and a structure to a series of personal and team behaviours that can optimise team performance. You may think they are natural and intuitive, but my observations in clinical practice are that they are not. The ZPS structure encourages all members of the team to understand and engage in the initial phases of resuscitation and to collectively optimise performance. Remember that not everyone is as keen, able, expert or as wonderful as you and I (erroneously) think we are. A common language that speaks to all team members irrespective of seniority or experience is clearly a good thing.

10 in 10

A team is far more than the combination of skills, knowledge and people within the room. For a team to function effectively they should have a common purpose based on a shared mental model of what is happening, why it’s happening and what they are collectively trying to do about it.

In the preparation phase of ZPS we discussed the three phases of situational awareness and how these can be articulated to the team but as we all know resuscitation can be a non-linear process that evolves and changes over time. Inevitably this means that the mental model that we shared as part of the ZPS becomes rapidly outdated and needs refreshing. There are several different models to deliver this but we like the simple 10 in 10 model. It stands for 10 seconds every 10 minutes and represents the need for the resus team to touch base on a regular basis to reaffirm or change the collective mind set.

Take at least 10 seconds, at least every 10 minutes to reform the team’s shared mental model

In practice it’s often a little longer than 10 seconds, and in truth it may not be exactly 10 minutes as there may be times when you need to do it more frequently. The point is that you should be aiming to do this at least every 10 minutes.

Here is a suggested checklist led by the team leader for the 10 in 10 strategy

- Recap on what has been achieved (or not) do far

- What’s happening now

- Agree next most important steps

- Prioritise next steps (with indicative time lines if possible e.g. we need to be ready to go scan in 10 minutes)

- Allocate specific people/kit/resource to achieve next steps

‘Fly the patient’ and then think

In general I’m not a big fan of aviation/medicine analogies. The ED in particular is a long way from the rules and resources accorded to the airline industry and I’ve been a bit of a sceptic in terms of mimicking the airline industry. It’s my belief that we really can’t do that on our current resources. That said there are some principles that do transfer over to the resus room. One such strategy is the axiom to deal with inflight emergencies

- Aviate

- Navigate

- Communicate

This axiom makes sense. There is no point working out where to go if you can’t stay in the air to get there, there is no point telling anyone what’s happening or where you are going until you know where you are. In most commercial aviation settings where there are two pilots these tasks are often separated and shared. One pilot, typically the junior pilot, flies the plane. Their job is to keep the aircraft in the air and their focus is ensuring that happens for as long as possible. The other pilot then seeks to navigate, communicate, problem find, problem solve and hopefully resolve the situation.

In my friend John Paddon’s words (Senior Captain, trainer and assessor)

‘Under high workload situations we teach pilots to offload. So hand over control and let the other pilot fly the aircraft. This then gives you as the Captain more capacity to assess the situation (i.e. increasing his situational awareness) allowing them to make more informed decisions and increase their ability to solve problems.’

How does that work in the resus room? I would argue that in many cases there is simply not enough cognitive bandwidth to run the minute by minute resuscitation and to work out how to get out of whatever resus loop we happen to be in.

Similar to this is another aphorism that I picked up from Cliff some years ago. When we think about Life Support then in many cases it is exactly that, a support system for life, which in many cases is linguistically and philosophically different from managing the underlying problem. Let’s think about cardiac arrest management. We can philosophically divide out the management of the code (cycles, timings, drug doses, shock cycles, defib processes) from the broader cognitive work needed to determine why this happened, what the underlying cause is and how we resolve the underlying problem in the short, medium and longer term. I would suggest that trying to run a code whilst also trying to work out how to solve the underlying problem is like trying to be a one man band. It’s a great party trick but very few people can do it and it’s nowhere near as good as the real thing.

It’s also worth mentioning at this point that the person best suited to fly the patient is the most capable person in the room. Bizarrrely this task is often allocated or assumed on the basis of seniority and/or job. Just for the record there is no reason whatsoever why this role cannot be conducted by a member of the nursing team.

The bottom line is that an effective resus requires minute-by-minute monitoring of the situation with the patient AND a slower, more thoughtful, more long-term view of where the overall resus strategy is heading.

A great resus team will combine the 10 in 10 principle with the Fly the patient principle to update the entire team on a shared mental model of resuscitation on a regular basis.

Peer review

Let me start with a question. Are you better at medicine than Roger Federer is at Tennis? I’m hoping that for the majority of you the answer will be no. You might be the most awesome ‘resuscitationist’ (if there is such a thing as a resusictationist) in your hospital but it’s unlikely that you’re the best in the world. The reason I ask this question is that Roger, like most if not all top level sportspersons, has a coach and there’s a very good reason for this. Put simply you are a really bad judge of your own abilities. You probably overestimate your strengths and underestimate your weaknesses. You are almost certainly completely blind to your incompetence in some areas of your practice. There’s nothing really to be embarrassed about though, it’s the same for everybody else too.

Let’s think about why that is.

- You compare your performance in any given scenario against your own personal values, experiencies, knowledge and skills. That can in no way be objective.

- You estimate your own performance on the basis of your memory of the events as the occurred which is radically different from the reality of what happened. Not only that, but our memories change over time as we reprocess and edit what happened. Most of us think that we can accurately remember events, but there is good evidence that we can’t. Dan Kahnman has a great presentation on this which delves into the difference between experience (what actually happened) and memory (what you remember happened).

3. You judge your decision-making abilities based on what you experienced at the time yet we know that most of us will only be able to experience or witness a component of the overall scene and experience. Situational awareness is a personal perspective and not a team one and so you judge yourself against your own personal situational synthesis and that’s biased.

4. You are emotionally tied to the event and thus lack objectivity. Emotion can cloud your judgement in several ways. A particularly tragic case (e.g. severe paeds trauma) will influence your emotions, your recollection and interpretation of events. At a personal level you may err towards optimism or pessimism, focusing on positive or negative aspects of what happened. Lastly you may be a narcissitic fool (we’ve all met them).

Here is a basic downloadable checklist you can use for observed feedack. There are others available or you could develop your own. In reality this is just a starting point for a conversation between experts as opposed to a required set of critieria

The bottom line is that you are a terrible judge of yourself. You lack the perspective, objectivity or the awareness needed to give yourself feedback. Sorry.

Peer review can work in sim settings OR in real life situations.

Sports are different of course. Feedback works in sports at a very basic level when you find out whether you win or lose (evaluative feedback), and of course there are the fans (appreciation feedback), but there is also the type of feedback that we refer to as ‘coaching’ which is the key to improving performance. This is why sport has coaches, it’s why musicians have teachers, and it’s why we don’t, or at least we certainly don’t once we get to be the sort of senior person who is likely to be running a resus team.

There are exceptions of course. One of the most common is in prehospital care in the UK and abroad. PHEM services do take time to objectively review cases with peer feedback, review and governance. There is much that we could learn from them.

So we need a solution, a practical and pragmatic way that we can ensure that we get feedback on our performance, and particularly for those of us taking on leadership roles in the ED. Our solution is peer review in the resus room. We don’t have the money or time to employ coaches, but we do have colleagues who have expertise and understanding in what we do and these are the resources that we can make available. The model is very simple, when a standby case comes in the lead consultant invites another consultant into the resus room to observe and take notes on what happens. We have used a variety of tools to do this, including a human factors observation tool developed by the college, but the point is that the observer looks at the overall performance of the team and the team leader. They then feed this back to the team leaders after the event and after the team debrief.

Interestingly we initially thought that this system would most benefit the person who was being observed, and there is some truth in that. I have been helped to change some of my behaviours as a result of the feedback, but in truth, and in common with others who have taken part it is often the person doing the observation who benefits most. We think this is because the observer has the time and cognitive bandwidth to compare and contrast what they see against what their own personal practice is. It is a means of opening your eyes to areas where you may be unconsciously incompetent. Peer review is not just about finding errors or problems, it’s also about seeing and then copying excellence.

In summary, unless you are as good at medicine as Roger Federer is at tennis then you don’t need a coach. If you’re not that good then you need to find one, and they are probably in the office next door. Go speak to them and make a resus date.

Hot Debriefs

This is not the time to go over the evidence for debriefs, let’s take it as read that debriefs are a good thing. We need to understand what happened, to look for good practice and areas for improvement and to share and then consolidate these learning principles. We also need to make sure that we look after our teams as we know that working in critical care is tough and leaves us exposed to moral injury.

So, if it’s obviously such a good idea why do we not do it? Arguably it’s because we struggle to find the time, space and systems to do so. We also arguably only debrief the strange and upsetting, rather than the relatively routine. We need to challenge these beliefs and use debriefs to improve practice.

There are a number of problems that commonly crop up with getting debriefs done in the ED.

1. We often lose people from the department before we can debrief. This is a common problem, but does it really matter that we get everyone there? Arguably we would really want everyone there, but in reality it can’t happen so don’t worry about it. So long as you have a critical mass of people (and ensure it’s multiprofessional) then go for it as soon as possible to the end of the event.

2. Who leads the debrief? In most cases the team leader takes on this role, but they are perhaps conflicted in this role and not best placed to do it. In an ideal world a separate person, perhaps the peer reviewer mentioned above, would be the best person to do it, but in reality it’s OK for the team leader to do it.

3. It can be a bit random. That’s true if you let it go completely free-form, but there are tools that you can use to improve the structure. One tool that we have reviewed recently and will be adopting in Virchester is the STOP5 tool from Edinburgh. This was developed by Craig Walker and colleagues and gives a structure to a debrief that can be delivered after most if not all significant resus events. Here are some top tips from Craig based on his experience of using it in Edinburgh.

- Always read the preamble out loud (helps set the tone and establish an air of genuine curiosity and desire to improve + intro to others

- Keep it short. You should be able to do this in 5 minutes as a team. If you notice that individual members need more in depth support then do that individually later.

- Ask someone other than the team leader to read out the preamble to encourage people other than the team leader to speak. There is no reason for the team leader to also lead the debrief.

- You can use the debrief tool in the whole range of cases, but there are a few where it should be routine: cardiac arrest, major trauma, severe sepsis are good examples.

- Your senior leadership need to buy into this as a model. Not everyone will want to use it, but if it is well led it can become routine and ‘expected’ by all.

Click here for a downloadable version of the poster courtesy of Craig Walker and his colleagues in Edinburgh Hot Debrief Poster V2 April 2018

You might also want to review a more up to date version from Kirsten Walthall that is a little less like Pendleton’s rules. I think this version has some advantages and alsolinks into clinical governance well

What, Why, How.

Let’s summarise the key points from the talk and review the actions that you can use to make a change in the quality of your resuscitations.

| What’s the problem? | Why is this important? | How are we going to improve this? |

| We sometimes struggle to prepare well for resus patients | We need the team to prepare well and to predict the clinical course. We can do this as soon as we know anything about the patient. | Use the Zero Point Survey checklist prior to the primary survey to optimise initial resuscitation team actions |

| Resus is a non-linear event (chaotic even). Even a well briefed team can rapidly lose track of the overall resus strategy. | A team with a shared mental model has a shared purpose and thus can optimise their resuscitation efforts | Use the 10 in 10 principle to regularly and routinely stop the team and collectively reframe the mental model. 10 seconds every 10 mins. |

| How do you know if you’re any good and how do you get better? | You can’t know yourself, you need help in the form of a coach – but who’s your coach? | Start peer review in the ED for resus cases. Get a colleague to watch you and give structured feedback. They will learn as much as you will. |

| We know debriefs are good, but we don’t seem to have a mechanism to do them routinely. | Debriefs are a way of consolidating knowledge, identifying good practice and spotting error. We really should do it | Use a structured debrief tool designed for rapid, consistent and safe debriefs. Use the STOP5 checklist. |

| There is just too much going on in a big resus to keep track of what’s going on! We often run out of bandwidth | There are 2 main themes in any resus. Keeping the patient alive and sorting out the underlying problem. | Use the Fly the Patient principle. Divide tasks into life support (process) and diagnostics/therapeutics (strategy) |

The Mindset of the Resuscitationist.

Many of the elements here are described in an excellent paper recently published in Emergency Medicine Clinics. I strongly recommend that anyone interested in improving their resus skills reads and digests this paper.

vb

S

References

1.Reid C, Brindley P, Hicks C, et al. Zero point survey: a multidisciplinary idea to STEP UP resuscitation effectiveness. C. 2018;5(3):139-143. doi:10.15441/ceem.17.269

2.Carley S. JC: The Zero Point Survey. Optimising resuscitation teams in the ED. St Emlyn’s • St Emlyn’s. St.Emlyn’s. http://www.stemlynsblog.org/jc-the-zero-point-survey-optimising-resuscitation-teams-in-the-ed-st-emlyns/. Published September 30, 2018. Accessed October 9, 2018.

3. Simon Carley, “New Zero Point Survey Video from Cliff Reid. St Emlyn’s,” in St.Emlyn’s, September 16, 2019, https://www.stemlynsblog.org/more-on-the-zero-point-survey-from-cliff-reid-st-emlyns/.

4. EM:RAP on the Zero Point Survey https://www.emrap.org/episode/emrap2020april/zeropointsurvey

5. The Mindset of the Resuscitationist https://www.emed.theclinics.com/article/S0733-8627(20)30058-4/abstract