Written by Anna Colclough, Nick Mani, Rachel Liu & Cian McDermott

Edited by Cian McDermott @cianmcdermott

We had a super interactive RCEM Clinical Leaders Point-of-Care Ultrasound Zoom call on Thursday April 23 2020. This session peaked with 308 international participants logged on but many were watching in groups so likely to have been lots more tuned in! No longer Cinderella’s ugly sister compared to Echo, lung ultrasound (LUS) is clearly a hot and critical topic!

The speakers were Anna Colclough (@drspando), Nick Mani (@EveryOneNoOne1) and Rachel Liu (@RubbleEM) with the session chaired by Simon Carley (@EMManchester).

We could not reply to all the questions on the feed so have summarised our thoughts for you

St Emlyn’s covered LUS in COVID-19 in March 2020 but given the level of interest it is useful to serve you up with a refresher! This post explains our experiences using LUS as we deal with COVID19

Is the recording available online?

Yes! This link will redirect to the RCEM member’s website to view the entire Zoom video. You do need to be an RCEM member of fellow to view it though.

Can you share the most important research papers on this topic?

This is a new disease and the evidence is still being collected on LUS in COVID-19. The world is learning but here are a selection of the most high impact research papers expertly appraised by Dr Nick Mani

- Tierney et al1 [doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004124]

- Huang et al2 [doi : http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3544750]

- Peng et al3 [doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6]

- Lu et al4 [doi:10.1055/a-1154-8795]

- Volpicelli et al5 [doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06048-9]

- Smith et al6 [doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15082]

- Poggiali et al7 [doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200847]

- Peng et al8 [doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02856-z]

- Volpicelli & Gargani9 [https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00171-w]

Is risk stratification possible with LUS?

Yes. Well, maybe!

As we learn about LUS in COVID19, it is clear that it is a complex disease

Read this paper9 from Giovanni Volpicelli (@giovolpicelli) & Tomas Villen (@TomasVillen) – they describe 4 broad disease categories

| Category | LUS findings |

| A – Low probability of COVID19 disease (normal lungs) | Regular sliding A-lines observed over the whole chest Absence of significant B-lines (i.e. isolated or limited to the bases of the lungs) |

| B -Pathological findings on LUS but diagnosis other than COVID19 most likely | Large lobar consolidation with dynamic air bronchograms Large tissue-like consolidation without bronchograms (obstructive atelectasis) Large pleural effusion and consolidation with signs of peripheral respiratory re-aeration (compressive atelectasis) Complex effusion (septated, echoic) and consolidation without signs of reaeration Diffuse homogeneous interstitial syndrome with separated B-lines with or without an irregular pleural line Patterns suggestive of specific diagnoses: – Cardiogenic pulmonary edema – diffuse B-lines with symmetric distribution and a tight correlation between the severity of B-lines and the severity of respiratory failure (anterior areas involved in the most severe conditions); in this case distribution of B-lines must be uniform; extending the sonographic examination to the heart will support the alternative diagnosis – Pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial pneumonia from alternative viruses – the pattern has greater spread and there are no or limited “spared areas” (alternating normal A-lines pattern). Chronic fibrosis – diffuse irregularity of the pleural line |

| C – Intermediate probability of COVID19 disease | Small, very irregular consolidations at the two bases without effusion or with very limited anechoic effusion Focal unilateral interstitial syndrome (multiple separated B-lines) with or without irregular pleural line Bilateral focal areas of interstitial syndrome with well-separated B-lines with or without small consolidations |

| D – High probability of COVID19 disease | Bilateral, patchy distribution of multiple cluster areas with the light beam sign, alternating with areas with multiple separated and coalescent Blines and well-demarcated separation from large “spared” areas. The pleural line can be regular, irregular or fragmented Sliding is usually preserved in all but severe cases Multiple small consolidations limited to the periphery of the lungs A light beam may be visualized below small peripheral consolidations and zones with irregular pleural line |

Perhaps you will combine your LUS findings with this workflow diagram in your ED? This one is used in Lewisham Hospital in London – provided by Dr Anna Colclough

We also suggest reading the narrative paper by Smith6 that describes where LUS fits in the COVID-19 patient care pathway, as well as LUS abnormalities that develop over time as the disease progresses and regresses

How to Approach the Lung Ultrasound exam

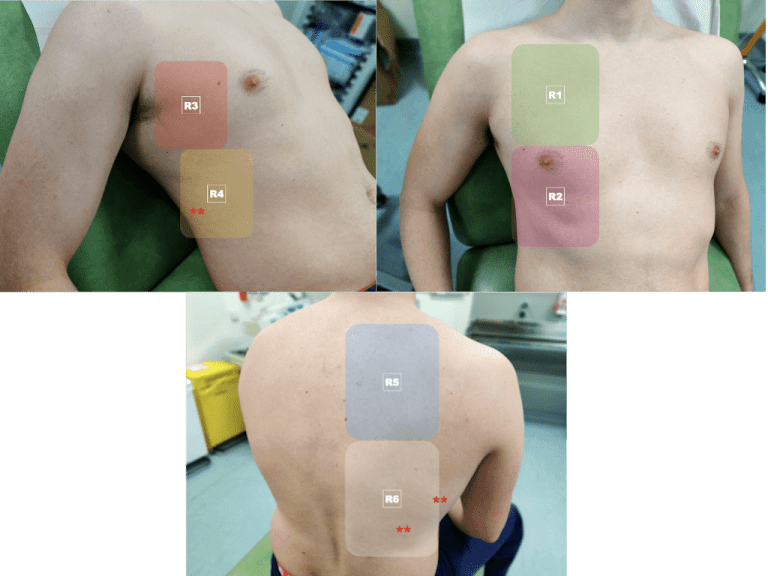

A scanning process that examines the posterior and lateral zones is most useful and we have been using a 12-zone protocol in line with most of our international colleagues. There are 2 zones in each of the anterior, lateral and posterior chest wall areas

Before scanning, try to establish a pre-test probabilty is COVID-19 likely or could another pathology be possible for example cardiac failure?

We do this all the time for our sickest patients and POCUS will help us narrow the differential diagnosis earlier and more accurately than standard clinical examination – it’s all about the Bayes don’t you know…

Choose a linear, curvilinear or phased array transducer. The curvilinear transducer allows a good compromise between depth (to view the lung artifacts) but also allows interrogation of the pleural line itself. Whatever transducer you choose, select a lung preset or an abdominal preset – make sure harmonics and compound image settings are off

If already performing focused echo, it is completely acceptable to use the phase array transducer also

Positioning your patient sitting up or semi-recumbent. Using a posterior to anterior approach may yield earlier results

Scan in the sagittal plane (pointer facing the patient’s head). Slide and sweep the transducer within each zone to look for artifacts and pleural abnormalities. Ensure the transducer is held perpendicular to the pleural surface, this may not be perpendicular to the skin and you should fan the transducer to achieve a sharp screen image

In the lower lateral zones interrogate the most inferior recesses of the lung to look for pleural effusions – large effusions are not usually found in COVID19

To examine a stretch of pleura, rotate the probe to a transverse position to lie between the rib space

Decontaminate transducer and consider leaving a dedicated US machine in your COVID zone

Report your findings in the context of your pre-test probability

LUS findings for COVID19

We covered the LUS abnormalities in an earlier St Emlyn’s post and by now there is an abundance of online videos showing these, collated using #POCUSforCOVID. Check out the most comprehensive collection of resources on Zedu’s homepage

Lung US

The normal A-profile is lost – that’s the bat-wing appearance we see in healthy patients

Look instead for B-lines in discrete patches, in more advanced disease these coalesce and become confluent. Disease is most typically found in the lower posterior and lower lateral zones of the thorax

The pleural line becomes irregular and develops a fragmented appearance as the alveoli become inflamed.

Interruptions in the pleural line occur with spared sections of pleural between. Sections of pleural line may also appear depressed or completely chaotic with a “crazy paving” appearance

As the disease progresses small consolidations appear beneath the pleural line and in more severe cases dense consolidated (hepatization) lung can be seen with a solid tissue-like appearance with brightly reflective air bronchograms within the darker tissue

Effusions are uncommon but may be small and localised around the areas of affected pleura

Echocardiography

COVID19 is thought to be a pro-thrombotic disease and pulmonary emboli and Covid 19 coexist in a significant number of patients. Echocardiography may demonstrate an enlarged, hypokinetic right ventricle exerting pressure on the interventricular septum and deforming the left ventricle from a ‘donut’ to a ‘D-shape’ on a parasternal short axis view. You may even see a ‘thrombus in transit’ form the right atrium to the ventricle

DVT

As a prothrombotic disease, deep vein thrombosis is likely to be a common coexisting pathology. Point of care compression sonography may guide the need for more aggressive anticoagulation, In practice, it is more likely that you will detect a DVT that indicates that a PE may be present. There are a number of international studies ongoing to investigate the prevalence of VTE in COVID19

Splenic rupture

There have been cases reported of splenic rupture in COVID19. Free fluid may be detected at the paracolic gutters on FAST scan. It is important to extend your scan to visualise the caudal tip of the spleen and liver to see earliest collections of intra-peritoneal fluid

Are the sonographic features specific to COVID19? Do you see them with any other condition?

The sonographic features in COVID19 are similar to any other viral pneumonitis including influenza, H1N1 or even RSV bronchiolitis in a child. However due to the current incidence and prevalence of COVID19, the specific changes on LUS will likely represent COVID until proven otherwise

Volpicelli has described a B-line configuration known as a light beam in his most recent paper – this is thought to be specific for the acute phase of active COVID19

Tell me more about US machine decontamination

It is recommended that you use a modern touch screen US device, and that it is specifically designated to the triage/ hot zone /resus area of your ED. It is much easier to wipe down a screen rather than explore the nooks and crannies of a keyboard, believe me!

Many of us are using portable handheld US devices, it is quite easy to use a plastic sheath to cover the transducer and the display device in effect using a single sealed system. Afterwards, it is best to use disinfectant wipes to clean your equipment and let it dry for about 3 minutes before you use it again

For larger mobile cart-based devices, this is a bit more tricky, but it is possible to think out of the box and cover the unit with large plastic covers available from gardening/ DIY shops. Change the cover between the patient, and clean the machine with approved wipes and let it dry for the same period of time

I am worried about operator exposure to COVID19 when scanning, how can I reduce this risk?

This is definitely a concern but bear in mind that you should be able to complete a 12-zone scan and 2 views of the heart in under 5 minutes – this is almost the same length of time that it takes to don PPE!

You should wear PPE at all times when scanning as per local/national guidelines

Use a 2D barcode scanner to save time when entering the patient details – one zap on the barcode and you are done. Always enter your patient’s details – phantom scans are not allowed!

As the postero-inferior lung region is most likely to have been affected first, it is better to start your scan from behind the patient as they facing away from you, limiting your exposure if they cough

Record a video loop of each region individually, or as anterior/ lateral/ posterior on both sides. Step away from the patient/ environment, similar to echo in life support, and study the video/ images outside the room

LUS for COVID19 at Emergency Department Triage

Identification and early streaming of patients with likely COVID19 before entry to the ED has a number of benefits

Cohorting

Move COVID19-likely patients to areas with appropriate protective equipment for staff and separate them from vulnerable non-COVID patients who lack immunity

Avoid anchoring bias

Ruling out COVID19 early for patients who would otherwise be mislabeled at triage may prevent anchoring bias. Not everything in our ED is COVID19 and other important pathology co-exists such as pulmonary emboli and typical pneumonias. Using POCUS in a sensible and structured way will help prevent this

Risk stratification

Although there is of yet no clear role for LUS in disease prognostication, it may be used alongside the symptom timeline to identify patients at a higher risk of deterioration. If LUS shows widespread disease at day 3 to day 7 we suspect that this patient will be more likely to deteriorate as the disease tends to peak in its second week of symptoms. The converse is not always true however!

LUS Triage Process

1, Decide clinical pre-test probabilty

2, Perform a posterior zone to anterior zone scan

3, Allow for a normal amount of dependent B-lines in a patient with a moderate or low pretest probability. Consider all B-lines suspicious in those where the pre-test probability is high

4, Complete comprehensive 12-zone scans are necessary to rule in COVID19 in patients with a moderate or low pre-test probability but posterolateral zone scanning only may be sufficient in those with high clinical suspicion

6, Record the sonographic findings in a standardised reporting form including pre-test probability and overall impression. Make these findings available to the attending clinician

Training Programme Structure

Dr Anna Colclough has used this process in her ED in Lewisham Hospital to facilitate accreditation for LUS in COVID19

- Introductory lecture on LUS and LUS in COVID19 – there are many FOAMed resources available

- Face to face supervised practice on a normal subject with approved trainer

- RCEM e-learning on the Basic principles and ultrasound physics

- USABCD.org Basic LUS e-learning and self assessment

- Logbook comprising of 10 cases, 5 done with direct supervision

- Triggered assessment, performed with approved supervisor

- Quality assurance – monthly audit of scans, all reports are logged and external assessor from respiratory medicine performs monthly assessment

How POCUS is practiced in other countries…..

Dr Rachel Liu is an Associate Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut and she is a dedicated POCUS educator and thought leader in the US

She gave us a fascinating run down on how POCUS is managed in the USA, where it has been a mandatory component of Emergency Medicine residency training programmes for several decades

Rachel explained how her Emergency Department uses ‘middleware’ (QPathE) to provide a workflow solution and quality assurance for point of care US scans performed in the ED.

I’ll bet you did not realise that accreditation, credentialling and certification are separate concepts? I find that the term accreditation is widely used in the UK and with less clarity

- accreditation refers to suitability of a training programmes to provide proficiency in the delivery of clinical standards or educaiton

- certification is the proof an individual’s exeprtise

- hospital credentialing refers to the verification of provider qualifications (education, training and licensure)

- hospital privileging refers to authorization of specific scope of practice based on credentials and performance

North America is light years ahead of UK & Ireland in terms of POCUS education and training and although the healthcare system is different, there is much to be learned from their novel use of this technology

Notice how cardiac and LUS are integrated to patient care pathways in Yale New Haven Hospital System

Check out this excellent webinar if you would like to hear more from Rachel and you will also find her at @RubbleEM

Final messages about Lung US in COVID19

Our patients are in the most vulnerable position, but so are you as frontline healthcare workers

Lung US is a fantastic tool used to differentiate, discriminate and decide on the best course of action when assessing patients with suspected COVID19 in ED

If you are a patient with COVID19, do you want a tool that’s powerful & accurate, used by your doctor at the bedside and can be repeated as needed or would you prefer a series of inferior tests and imaging?

As an Emergency Medicine specialist doctor, you have the skills to use this diagnostic tool to literally ‘see with sound’ and enhance your clinical exam. Use it to tailor treatment to your sickest patients at an earlier stage

As the pendulum swings in coming weeks and months, there will be more undifferentiated presentations of dyspnea to our EDs. Lung findings are likely to be present for 1 month post – exposure but it is not clear at what stage the patient is no longer infected. Identifying those patients with COVID19 will be unlikely to be done accurately by triage discussion alone. LUS may be even more useful then than it is now!

Written by Anna Colclough, Nick Mani, Rachel Liu & Cian McDermott

Edited by Cian McDermott @cianmcdermott

References

- 1.Tierney DM, Huelster JS, Overgaard JD, et al. Comparative Performance of Pulmonary Ultrasound, Chest Radiograph, and CT Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure*. Critical Care Medicine. February 2020:151-157. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000004124

- 2.Huang Y, Wang S, Liu Y, et al. A Preliminary Study on the Ultrasonic Manifestations of Peripulmonary Lesions of Non-Critical Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19). SSRN Journal. 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3544750

- 3.Peng Q-Y, Wang X-T, Zhang L-N. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. March 2020. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6

- 4.Lu W, Zhang S, Chen B, et al. A Clinical Study of Noninvasive Assessment of Lung Lesions in Patients with Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) by Bedside Ultrasound. Ultraschall in Med. April 2020. doi:10.1055/a-1154-8795

- 5.Smith MJ, Hayward SA, Innes SM, Miller A. Point‐of‐care lung ultrasound in patients with COVID‐19 – a narrative review. Anaesthesia. April 2020:1.

- 6.Smith MJ, Hayward SA, Innes SM, Miller A. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in patients with COVID-19 – a narrative review. Anaesthesia. April 2020. doi:10.1111/anae.15082

- 7.Poggiali E, Dacrema A, Bastoni D, et al. Can Lung US Help Critical Care Clinicians in the Early Diagnosis of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia? Radiology. March 2020:200847. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020200847

- 8.Peng Q-Y, Wang X-T, Zhang L-N. Using echocardiography to guide the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Crit Care. April 2020. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-02856-z

- 9.Volpicelli G, Gargani L. Sonographic signs and patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia. Ultrasound J. April 2020. doi:10.1186/s13089-020-00171-w